Welcome! In this article, we delve into some essential questions about foodborne bacteria, specifically Salmonella and E. coli O157. Can these bacteria be transmitted in everyday places like toilets, or even during conversations at the dining table? While these bacteria are primarily known for causing infections through contaminated food, understanding their true transmission routes is crucial for food safety. Join us as we explore how foodborne pathogens behave and why they generally infect us only through food, shedding light on food microbiology and safe eating practices.

Do Salmonella and E. coli O157 Spread in Toilets or Through Conversation?

When discussing norovirus, we know that infections can spread not only through contaminated food but also via surfaces, such as towels in a public toilet. This means norovirus can indeed be transmitted through contact in the toilet. But what about Salmonella and E. coli O157?

Now, imagine you're having a meal with a friend who recently suffered from E. coli O157. Would you be at risk of infection from them through simple conversation at the dining table?

The answer is:

Salmonella and E. coli O157, as well as other pathogens often classified as foodborne bacteria, do not spread directly from person to person in places like toilets, nor do they transmit through conversations or the air. These bacteria only cause illness when consumed in contaminated food.

Why is that?

Is Food Required for Foodborne Bacteria to Cause Infection?

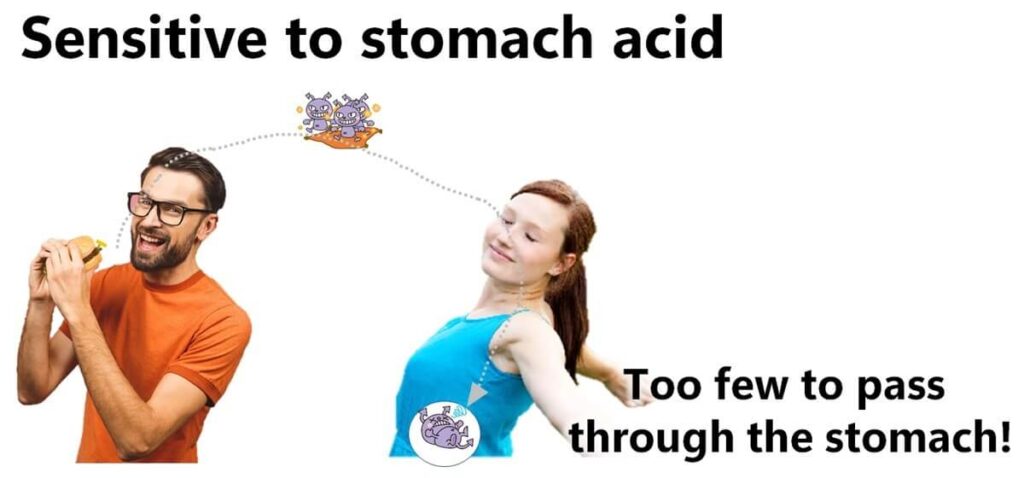

The answer lies in the infectivity of foodborne bacteria, specifically how many bacterial cells must enter our bodies to cause an infection. This infectivity depends on factors such as resistance to stomach acid, tolerance to bile acids secreted in the small intestine, competition with gut microbiota, and the ability to evade immune responses upon invading intestinal epithelial cells.

Among these factors, resistance to stomach acid is considered the most crucial. When foodborne bacteria enter our bodies along with food, they encounter the stomach's highly acidic environment. Gastric acid creates a pH level around 1 to 2, which is so acidic that it rapidly kills most microorganisms. At such a low pH, hydrogen bonds that maintain the three-dimensional structure of proteins break, causing protein denaturation. Since microbial cells are also protein-based, they cannot survive at this pH level.

Many microorganisms adhere to non-heated food surfaces. If these diverse microorganisms could easily invade our intestines, we would see the following consequences:

- The composition of our gut microbiota would alter significantly every time we eat.

- If pathogenic bacteria were present in the food, we would experience foodborne infections with each meal.

Thus, the stomach’s role in killing these microorganisms during digestion is vital for preventing infections.

While the stomach primarily functions as a digestive organ by breaking down proteins with pepsin, which is secreted there, the small intestine also secretes protein-digesting enzymes. From a digestive perspective, the stomach's role is not absolutely essential. However, from a microbiological viewpoint, without the stomach, we would lose its essential role in antimicrobial defence through stomach acid. In individuals who have undergone total gastrectomy due to conditions such as stomach cancer, digestion can still occur, yet their vulnerability to infections from ingested microorganisms is significantly heightened.

As mentioned, foodborne bacteria are primarily killed in the stomach. However, in cases where a large quantity of foodborne bacteria is ingested, a few cells may survive. These surviving bacteria can potentially cause foodborne infections once they reach the small intestine.

How Much Bacteria Floats in Airborne Dust?

With the context provided above, let's clarify why foodborne bacteria do not cause infections via toilet or airborne transmission.

Firstly, let’s consider how many bacteria might be floating in the air. For a basic understanding of microbial counts, please refer to our related article:

The Importance of Understanding Aerobic Plate Counts in Food

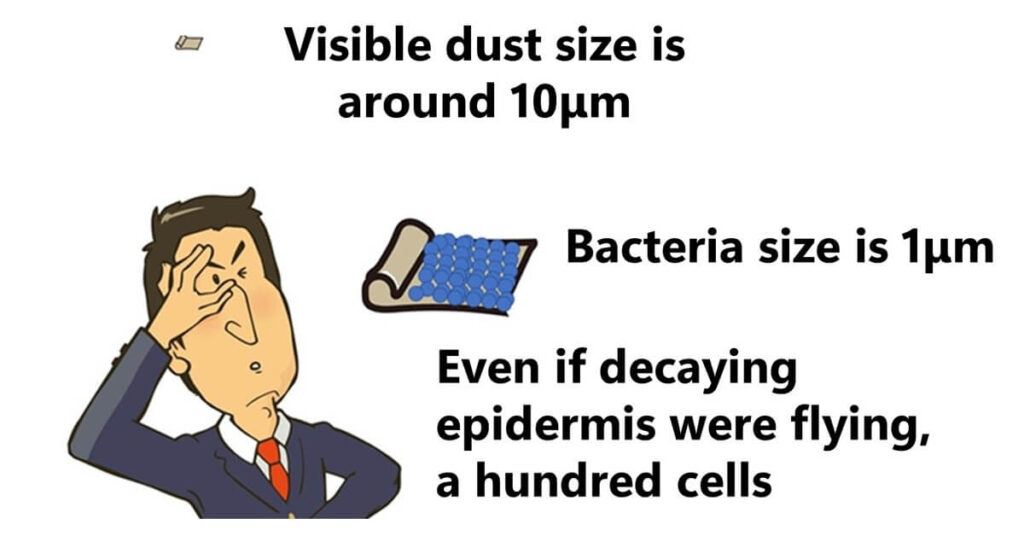

In simple terms, let’s perform a quick calculation. The size of visible dust particles is approximately 10μm square, while bacterial cells are around 1μm in size. Imagine a decaying animal or plant surface densely covered with microorganisms. Even if dust rises from this surface, the maximum number of cells that could become airborne would be around 10 × 10 = 100 cells. In other words, if one dust particle enters our mouth, it could carry around 100 bacterial cells. Assuming we ingest ten such particles, about 1,000 bacterial cells might enter the body.

However, realistically, it’s highly unlikely for foodborne bacteria, specifically in quantities of 100 cells or more, to enter our bodies from airborne dust due to these conditions:

- Airborne dust typically does not originate from surfaces of severely decaying animals or plants (an uncommon scenario in everyday environments).

- Not all bacteria adhering to dust are foodborne bacteria (the chance of this is almost zero).

Though no precise experimental data is available, it is practically impossible for more than 100 foodborne bacteria to enter the body from airborne dust (Note: the probability is negligible). Therefore, airborne transmission does not occur.

What If Foodborne Bacteria Were Resistant to Stomach Acid?

Let’s explore what would happen if foodborne bacteria had a high resistance to stomach acid.

As mentioned earlier, although it’s unlikely for large amounts of foodborne bacteria to enter the body via airborne dust, a few cells could still make it through. If these cells were completely resistant to stomach acid, we would likely suffer frequent infections from inhaling airborne dust.

In this case, the answer to the initial question—whether foodborne bacteria can spread in the toilet or through conversation—would be yes (see Notes 1 and 2).

Under such conditions, the fundamental principles of food microbiology as a discipline would be disrupted. Salmonella and E. coli O157 would no longer be classified as foodborne bacteria; they would instead be considered as airborne or person-to-person transmitted bacteria. This blog focuses on preventing and controlling microbial infections via food, which is at the core of food microbiology. However, if these infections could spread through other means, the very foundation of this field would no longer apply.

In summary, foodborne bacteria are defined by their lack of resistance to stomach acid. This is why they are specifically called “foodborne” bacteria.

Since foodborne bacteria are vulnerable to stomach acid, they need to enter our bodies with food in order to survive and multiply.

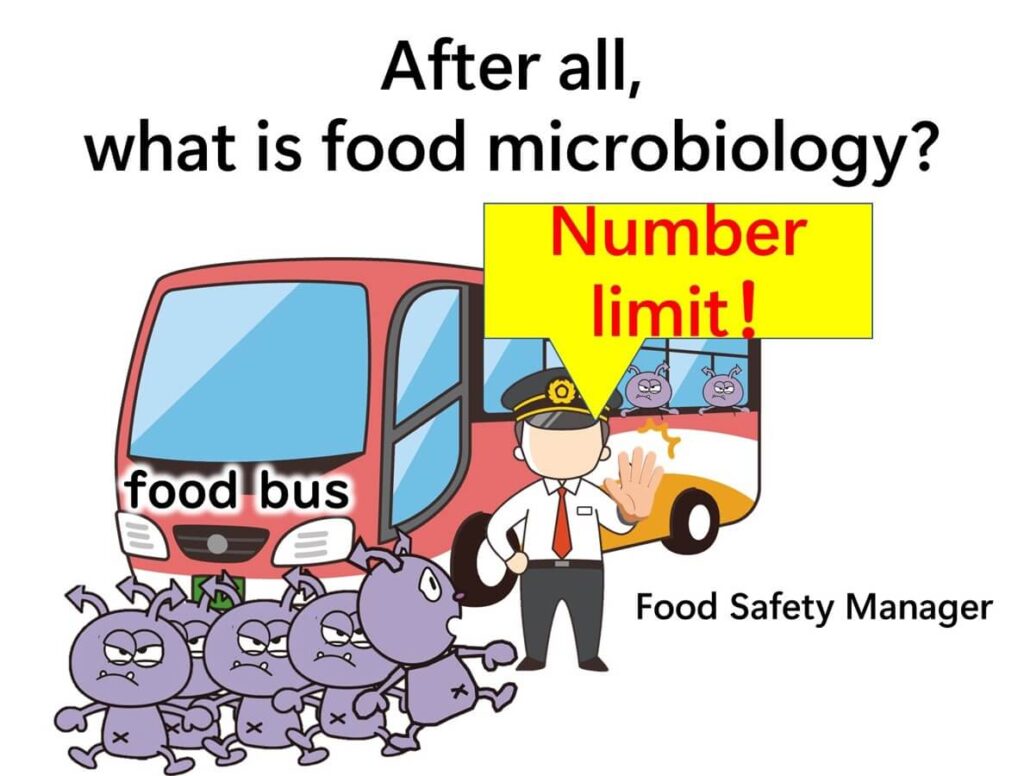

Think of food as a bus carrying a large number of bacteria. For these bacteria to cause an infection, they must board the “food bus” to enter our bodies.

In contrast, airborne dust is like a taxi – it’s much smaller than the food bus. Therefore, airborne transmission is unlikely to lead to an infection.

In essence, food microbiology can be defined as the study of preventing microorganisms from hitching a ride on the food bus. The aim is to keep our food safe and free from harmful bacteria.

Understanding foodborne bacteria and the principles of food microbiology enables us to take necessary precautions and enjoy our meals with confidence.