Metagenomic analysis is a powerful tool in microbiology, allowing researchers to examine the entire genetic composition of microbial communities without the need for culturing. However, not all methods traditionally referred to as metagenomics, such as 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing, strictly fit this definition. Unlike full metagenomic approaches, 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing targets a single gene, offering a highly efficient method for microbial community analysis, particularly in the food industry.

This article explores how 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing improves food quality testing and helps resolve microbial contamination complaints. Additionally, we discuss its potential for routine microbial monitoring and zone management in food factories. Discover how this sequencing technique is shaping modern food safety practices.

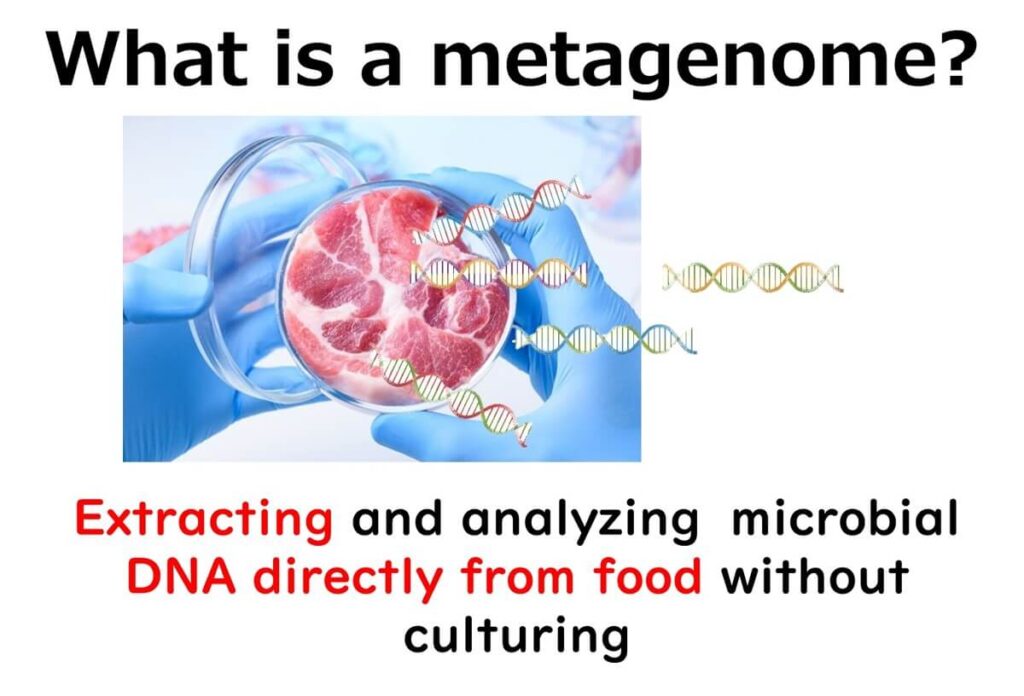

What is Metagenomic Analysis? Understanding Microbial DNA Extraction Without Culturing

Metagenomic analysis is a powerful method in microbiology that examines the entire genetic composition of microbial communities within a sample. Unlike traditional microbiological techniques, this approach bypasses culturing and directly extracts and analyses microbial DNA from food or environmental samples.

By sequencing the collective microbial DNA in a sample, metagenomics enables a comprehensive understanding of microbial diversity, including unculturable organisms that standard plate-based methods cannot detect. This technique has revolutionised microbial research and is increasingly applied in food safety, quality control, and contamination investigations.

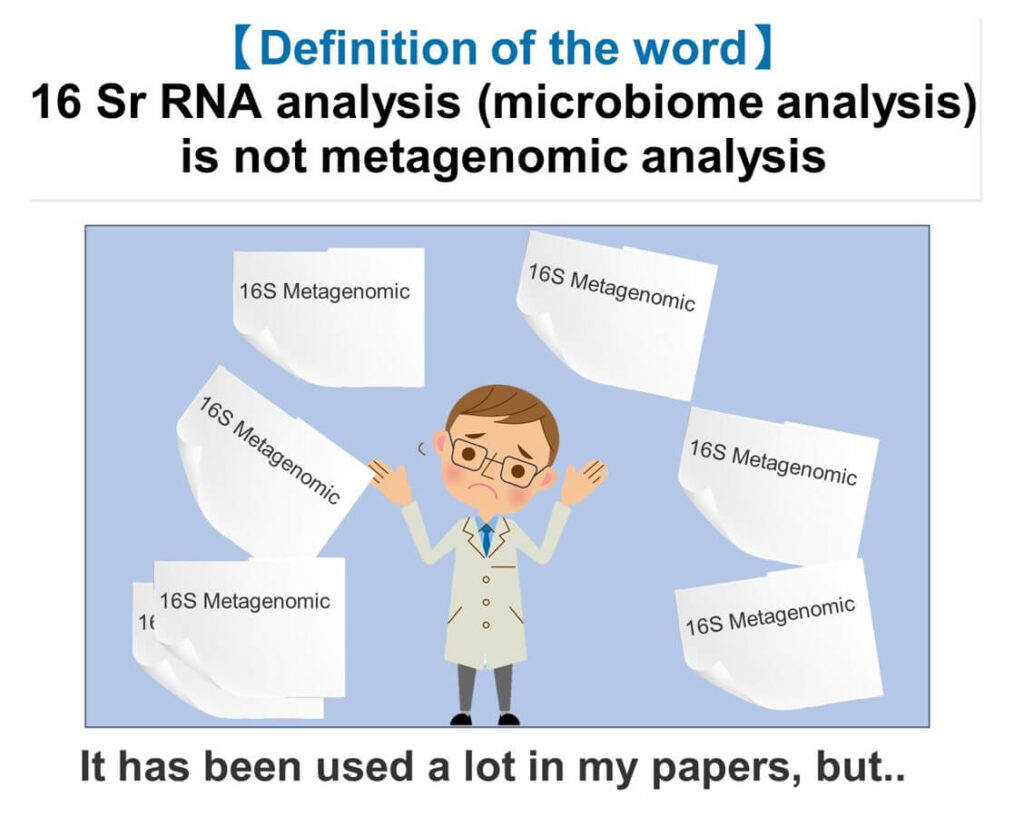

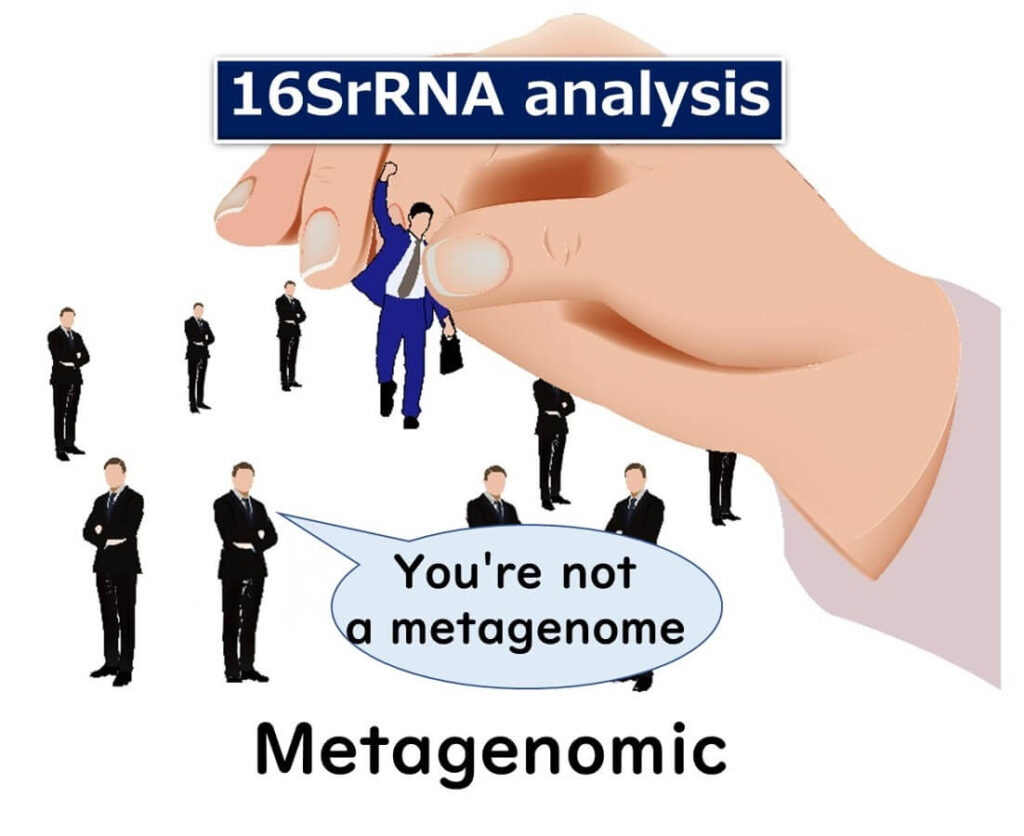

Why 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing is NOT Metagenomic Analysis

Traditionally, the analysis of bacterial communities using the 16S ribosomal RNA gene has often been labelled as metagenomics in scientific literature and online discussions. However, this classification is misleading. Unlike true metagenomic sequencing, which analyses the entire genetic content of a sample, 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing focuses on a single gene.

Despite its widespread use, experts in microbial genomics increasingly argue that this technique should be classified as metabarcoding or amplicon sequencing rather than metagenomics.

Recent discussions among leading microbial genome researchers have highlighted a crucial distinction:

Amplifying and sequencing the 16S rRNA gene does not provide a complete picture of the microbial genome and, therefore, does not meet the definition of metagenomics.

For a deeper dive into this topic, refer to:

16s rDNA targeted NGS is Metagenomics or Metabarcoding?

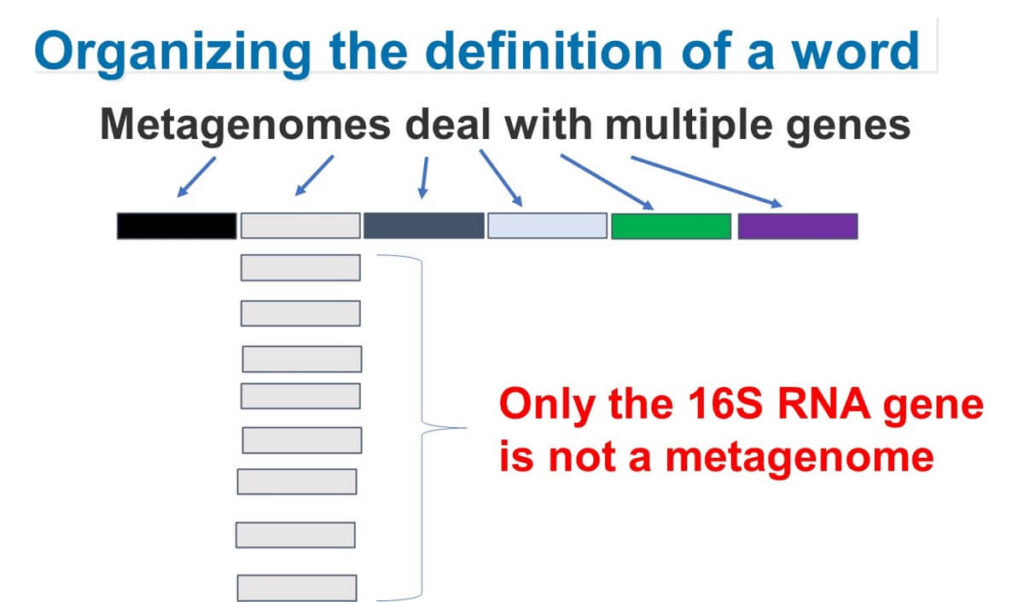

The key reason why 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is not true metagenomics is that it only analyses a single gene: the 16S ribosomal RNA gene.

Metagenomics, by definition, involves sequencing multiple genes or even entire microbial genomes. While some still argue that analysing microbial diversity from food samples qualifies as metagenomics, the dominant view among genomic experts is that this classification is incorrect.

Even if a sample is a "meta" sample (containing multiple microorganisms), analysing just one gene does not provide a full metagenomic profile.

Therefore, more appropriate terms for this method in the future would be 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing, 16SrRNA metabarcoding, or 16S rDNA analysis. For the sake of convenience, this blog will refer to it as 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing.

Applications of 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing in Food Safety and Quality Testing

How can 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing contribute to food safety and quality assurance in the food industry? This section examines its advantages, limitations, and potential applications in detecting microbial contamination and improving quality control.

1. Food Safety

When evaluating food safety, 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is currently not the primary choice. This is because real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and other established methods are already highly effective for detecting specific foodborne pathogens.

However, one major strength of 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is its ability to detect a wide range of microorganisms without the need to predefine target species. This broad-spectrum detection provides an advantage over qPCR, which relies on specific primers to identify known pathogens.

A key limitation of 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing for foodborne pathogen detection is its low sensitivity compared to qPCR. To ensure food safety, regulatory standards require detecting as few as 1 colony-forming unit (CFU) per 25 grams of food.

However, food samples often contain high levels of background bacteria. For example, if there are 10⁵ CFU/g of background microbes, detecting a single pathogen among them is technically challenging. Even with improved sequencing sensitivity, the cost of achieving such precision is significantly high.

Thus, for foodborne pathogen monitoring, PCR-based methods remain superior in sensitivity and cost-effectiveness. This makes 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing impractical for regulatory food safety testing.

2. How 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing Transforms Food Quality Testing

Unlike food safety applications, 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is highly valuable in food quality testing. This technique is essential for understanding microbial flora, which plays a key role in food spoilage, fermentation, and contamination tracing.

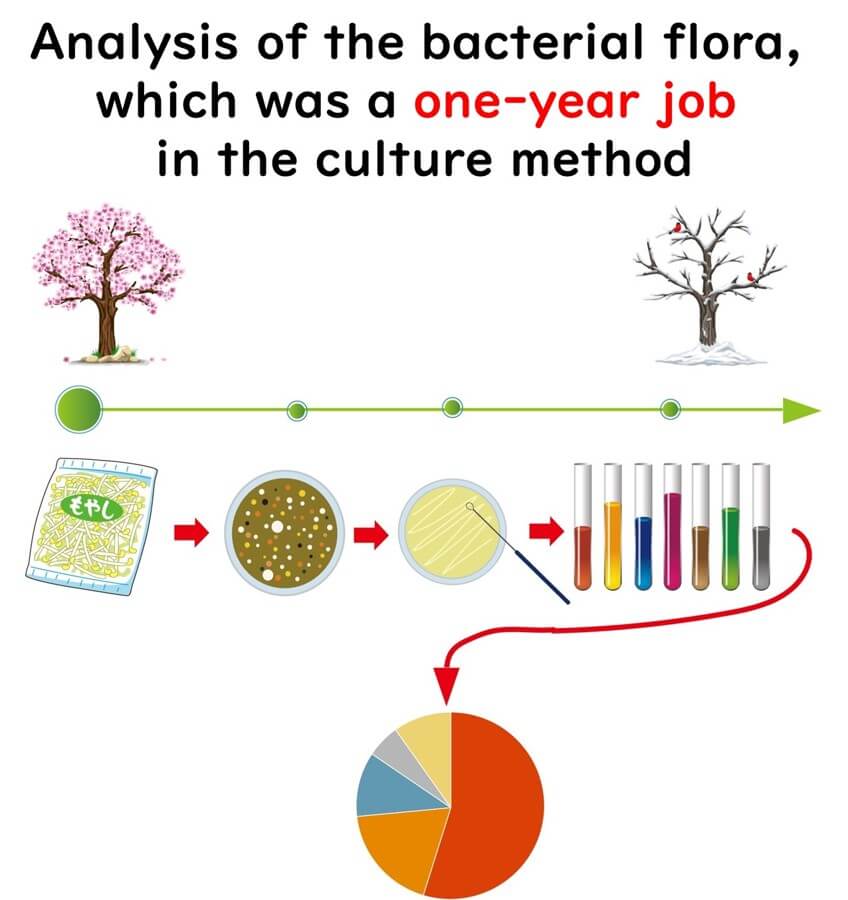

Before the development of next-generation sequencing (NGS), analysing the microbial composition of a single food sample could take an entire year of laboratory work. Now, with NGS-powered sequencing, the same task can be completed in just one day.

With NGS-powered 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing, the same microbial flora analysis that once took a year using traditional culture methods can now be completed in just one day.

This rapid and efficient approach is revolutionising food quality control, fermentation monitoring, and shelf-life assessment.

So, how can this technology be utilised in the food industry?

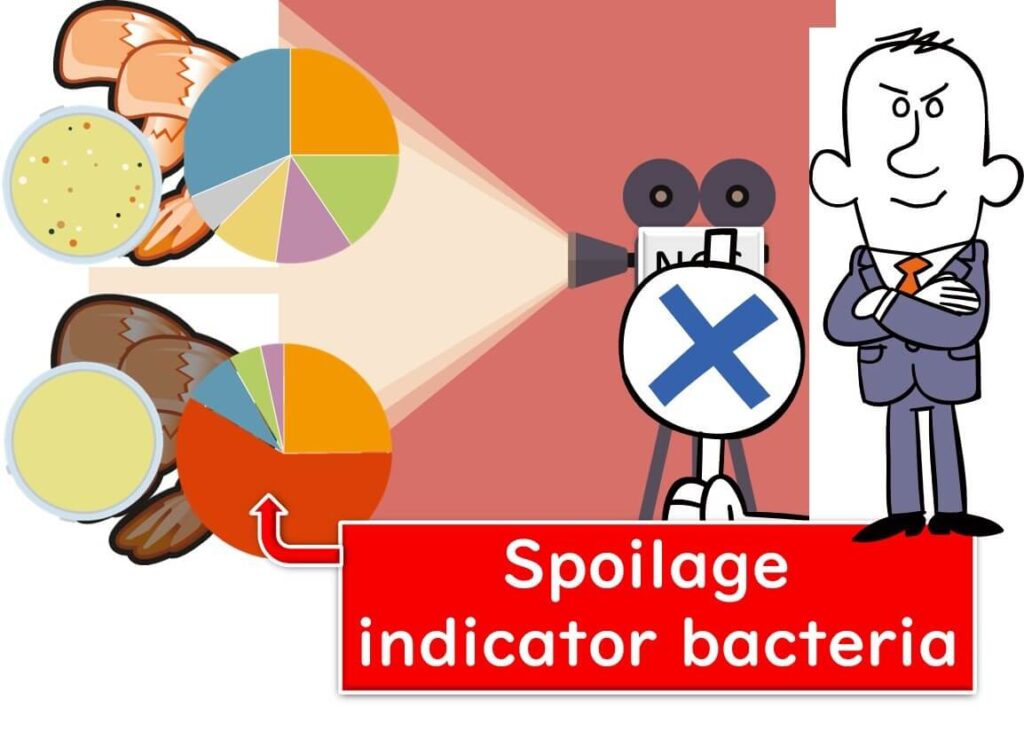

Routine food quality control typically involves total bacterial count testing and Escherichia coli detection. The total bacterial count method estimates the overall microbial load in food and production environments.

However, this approach only measures the quantity of bacteria, not their identity. This is similar to assessing airport security risks based solely on the size of luggage, without checking its contents.

In reality, even if two food samples have the same total bacterial count, their microbial compositions may be entirely different.

16SrRNA amplicon sequencing goes beyond simple bacterial counting—it provides detailed insights into microbial communities, much like an X-ray revealing the contents of a suitcase at airport security.

By identifying specific bacterial species, this method dramatically improves the accuracy of food quality assessment.

As with any technology, when it is technically challenging or expensive, its potential applications are not immediately apparent. However, once the technology becomes affordable and easy to use, its wide range of applications becomes evident. The same applies to the 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing technology made accessible by next-generation sequencers.

Below, I will outline my views on how this technology can be utilised.

Applications of 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing in Food Industry

Advantages of 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing

With 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing, DNA is extracted directly from food samples, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of microbial communities. Unlike culture-based methods, this technique detects both live and dead microbes, providing a complete picture of contamination sources.

Identifying the dominant bacterial flora—regardless of microbial viability—is crucial for tracing contamination origins and implementing effective countermeasures.

This information can help in formulating countermeasures. Accumulating past 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing data could even allow pinpointing contamination sources within a factory line.

While identifying bacterial communities alone might not immediately resolve the issue, it can narrow down potential causes. 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing serves as a guide to eliminate unlikely possibilities and focus on more probable ones. For example, using a smartphone to search for nearby restaurants in an unfamiliar city helps you know whether there are no restaurants nearby or several options. Similarly, narrowing down possibilities is a significant advantage of 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing.

Building a Contamination Database

A key advantage of 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is the ability to store and analyse digital microbial data for long-term tracking of contamination trends.

By comparing microbial profiles from different factories or production batches, food manufacturers can quickly pinpoint contamination sources and implement preventive measures.

Building a comprehensive microbiome database enhances food safety management and allows for faster resolution of future contamination issues.

Investigating Food Product Complaints

When unexplained quality issues arise in food products, 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing offers a powerful solution. Issues such as sliminess, gas formation, or swelling in packaged foods often lead to consumer complaints. However, traditional microbiological methods struggle to pinpoint the exact microorganisms responsible.

Before the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS), investigations relied on culturing general bacteria, selecting representative colonies, and identifying them manually—a process that was time-consuming and often failed to detect the true cause.

One major limitation of culture-based methods is the difficulty in selecting the correct growth conditions for the microbes causing the issue. If the wrong culture conditions are used, the target microorganisms may fail to grow, leading to false-negative results.

For example, in vacuum-packed chilled foods stored at 10°C, spoilage organisms may be anaerobic or psychrotrophic. Standard total bacterial count methods often fail to detect anaerobic bacteria, leading to misleading results.

Although regulatory guidelines prescribe specific bacterial count methods, these may not be suitable for evaluating spoilage under actual storage conditions. This uncertainty makes it challenging to determine the most appropriate testing approach.

Using PCA media for general bacterial counts might not accurately measure spoilage bacteria like lactic acid bacteria in the food. For lactic acid bacteria, nutrient-rich media like MRS agar are required.

Given these considerations, deciding on the appropriate culture conditions for each food product can be confusing.

Another critical limitation of culture methods is time consumption.

For example, investigating spoilage in chilled foods suspected to be caused by psychrotrophic bacteria requires low-temperature culturing, which can take several days to weeks. Even after incubation, additional time is needed to isolate and identify dominant microbial colonies, delaying quality investigations and corrective actions.

In cases like swollen packaged foods, the bacteria causing the swelling might have died by the time the product is submitted. In such cases, no microbes might grow, despite efforts to culture them.

Thus, relying solely on culture methods for investigating complaint causes has several issues, such as time consumption and the possibility of culture failure.

Tracking Microbial Contamination in Food Factories

16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is a powerful tool for monitoring microbial contamination in food factories. It enables routine tracking of bacterial flora on floors, production lines, and equipment surfaces after cleaning.

By identifying persistent microbial communities, manufacturers can detect high-risk contamination zones that are difficult to remove, enhancing hygiene control measures.

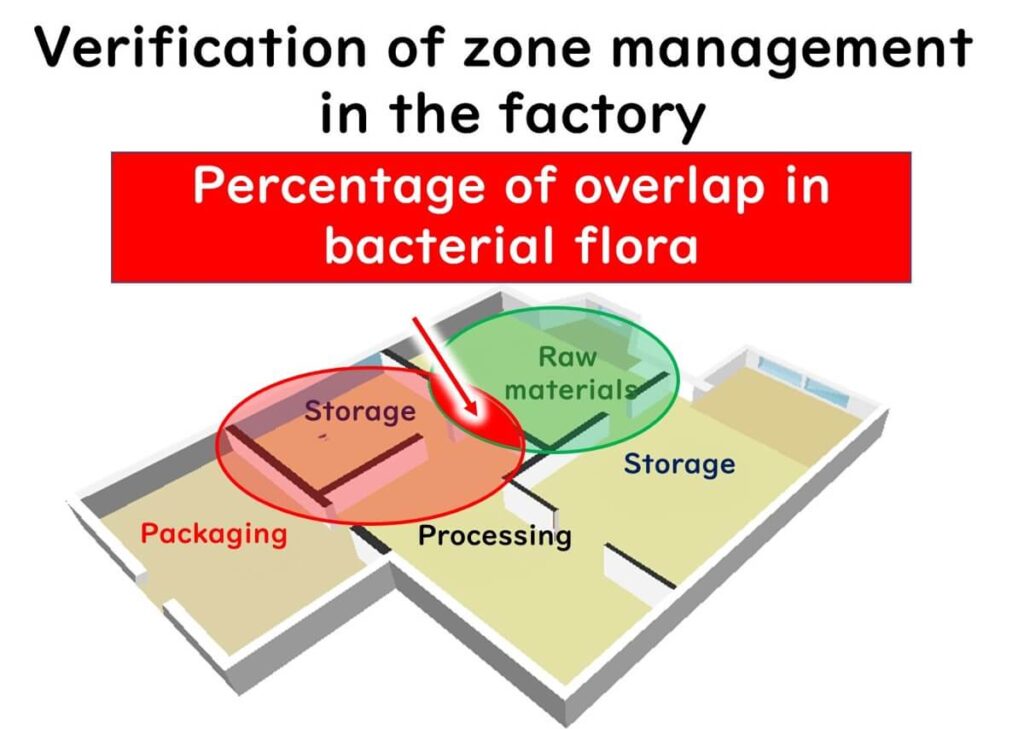

16SrRNA amplicon sequencing can also be used to assess the effectiveness of zone management in food factories by detecting cross-contamination between different production areas.

For example, sequencing raw material storage areas and clean packaging zones can reveal whether bacterial transfer occurs. If zone management is effective, there should be minimal overlap in the operational taxonomic units (OTUs) detected in each area.

However, if cross-contamination is frequent, the proportion of shared OTUs between zones will increase. In extreme cases, if the bacterial compositions are identical, it suggests a lack of proper separation between zones.

Using OTU overlap percentages as a quantitative metric, factories can refine hygiene protocols and environmental monitoring strategies to improve microbial control.

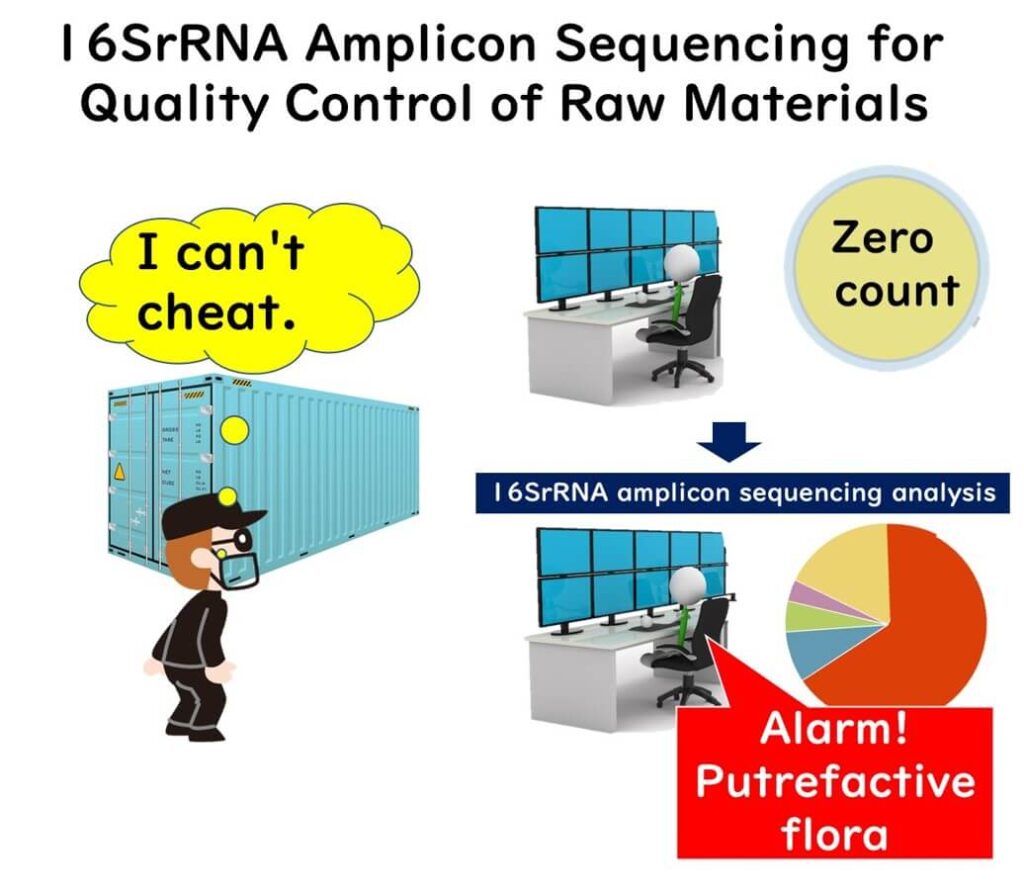

Microbiological Quality Monitoring of Raw Materials

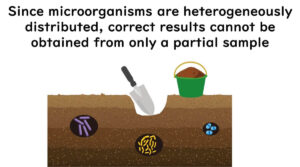

The microbial composition of agricultural products and seafood is strongly influenced by environmental factors. Before the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS), analysing microbial communities was time-consuming and impractical, limiting the use of microbes for raw material traceability.

However, with the advancement of NGS, it is now possible to rapidly profile bacterial communities in food, enabling traceability analysis based on microbial signatures. Although large-scale reference datasets are still developing, 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing holds great potential for determining the geographical origin and production conditions of raw materials.

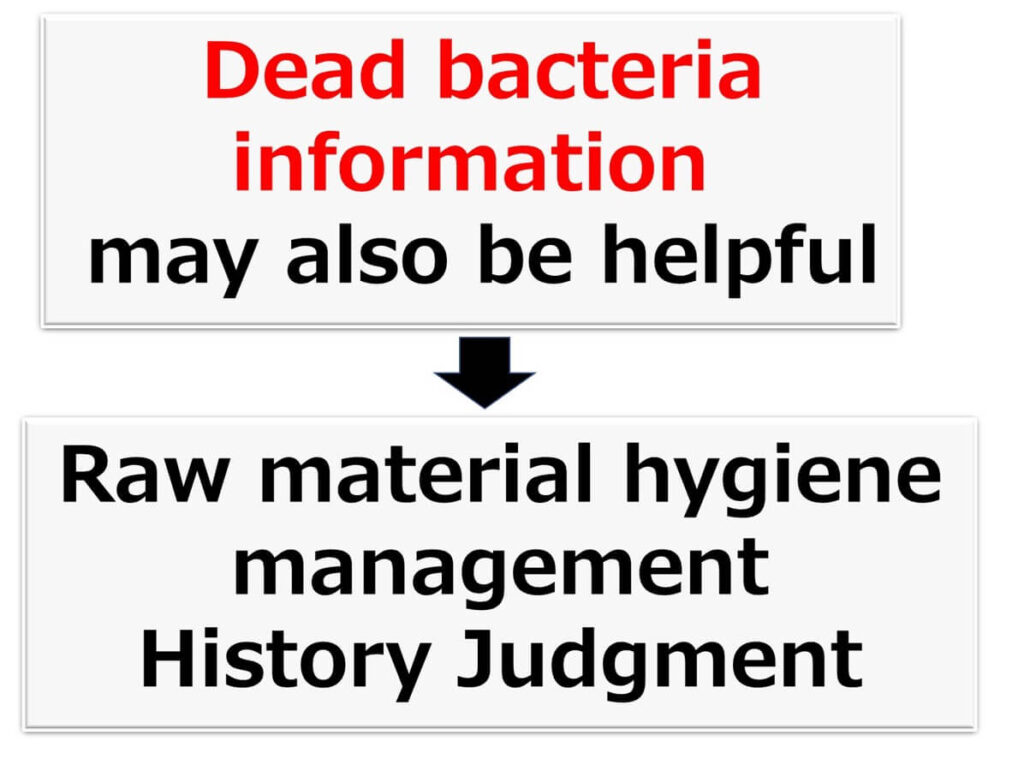

A common misconception about 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is that it detects the DNA of dead microbes, potentially leading to misinterpretation of microbial data. However, this feature is not necessarily a drawback—in fact, it can provide critical insights for food safety and raw material quality control.

For example, imported vegetables or meat may exhibit unexpectedly low total bacterial counts. Even if these products were previously in a state of decay due to poor sanitary conditions, sterilisation with sodium hypochlorite or other disinfectants can artificially reduce bacterial counts, masking the true microbial history of the raw materials.

In such cases, the receiving company could use 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing to analyse the bacterial flora, providing insights into the microbiological quality of the raw materials.

Spoilage Bacteria as Indicators of Quality Issues

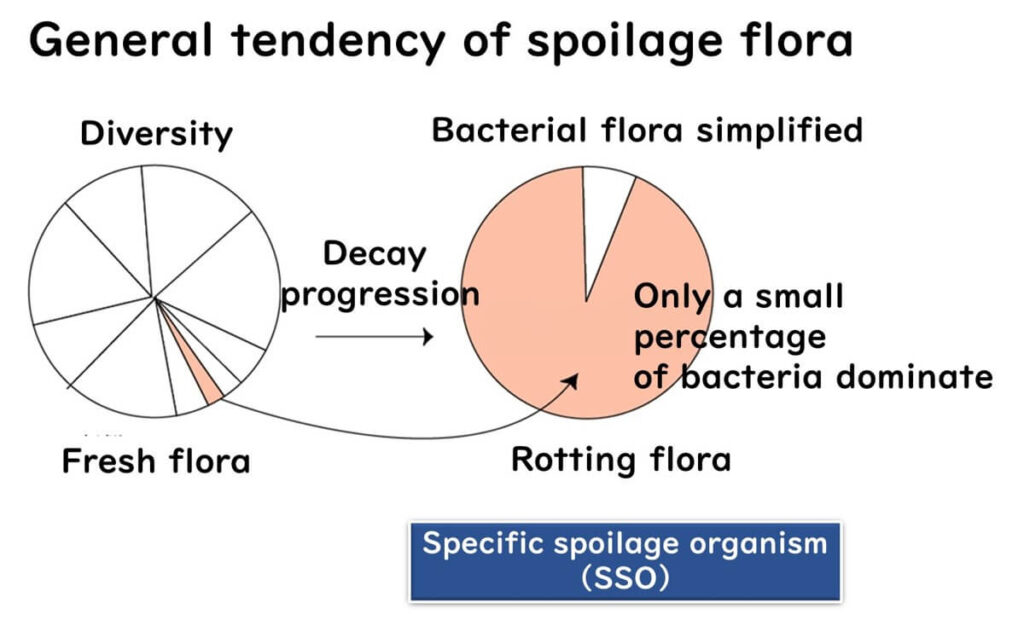

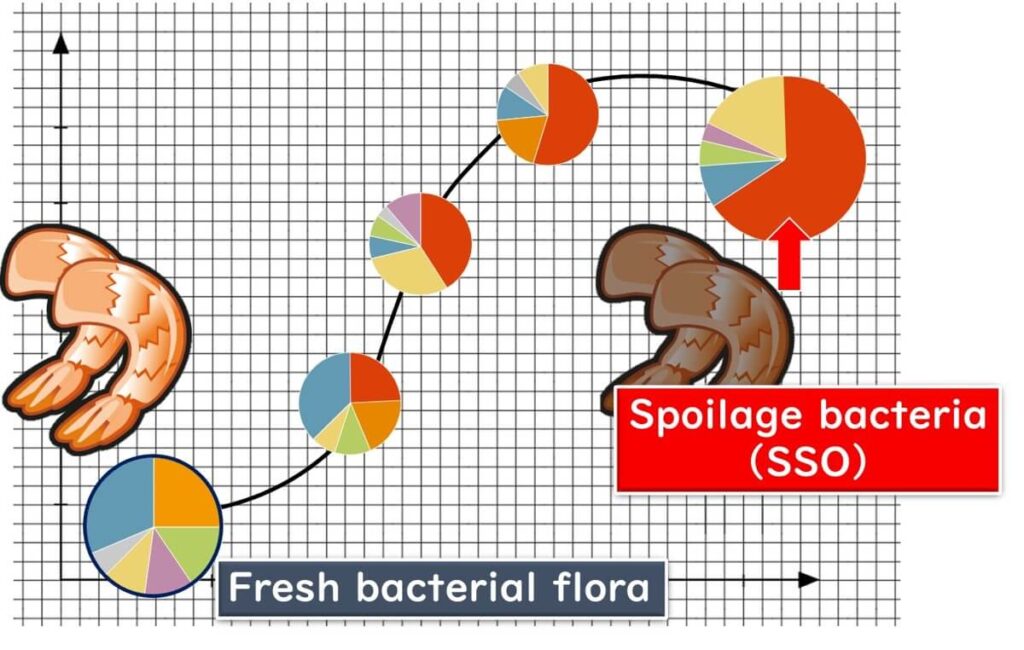

In fresh vegetables and seafood, the bacterial communities are diverse and complex. However, as spoilage progresses, the microbial diversity decreases, and specific spoilage organisms (SSOs) begin to dominate the bacterial flora.

These SSOs serve as reliable indicators of spoilage, allowing food manufacturers to assess raw material freshness and detect possible hygiene issues in the supply chain.

Thus, by simply examining the bacterial communities, one can assess the freshness or spoilage of meat and vegetables. If a company's analysis of incoming raw materials reveals simple bacterial communities or those characteristic of spoilage, it may indicate a history of spoilage.

By employing such techniques, companies can exert preventative pressure on their suppliers regarding the quality of raw materials.

By accumulating detailed data on the temporal changes in spoilage bacterial communities of raw materials, food companies can adopt the applications discussed here.

Important Considerations for Implementing 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing

Limitations of 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing: Distinguishing Live and Dead Microbes

One limitation of 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is its inability to distinguish between live and dead bacteria. This is because DNA from dead microbes remains detectable, which can sometimes complicate the interpretation of microbial data in food safety applications.

While some studies have attempted to extract RNA instead of DNA and use reverse transcriptase to generate cDNA for sequencing, these methods are still uncommon in practical applications. Additionally, ribosomal RNA remains stable even after bacterial death, meaning that even RNA-based approaches may not always accurately differentiate live microbes.

Therefore, when analyzing bacterial communities in food samples, it is crucial to consider the possibility that detected DNA may originate from dead bacteria, potentially impacting quality control decisions.

Further insights into why DNA persists in the environment even after microbial death, refer to the section "Understanding the Limits of PCR Detection in Food Microbiology"

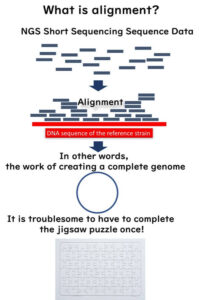

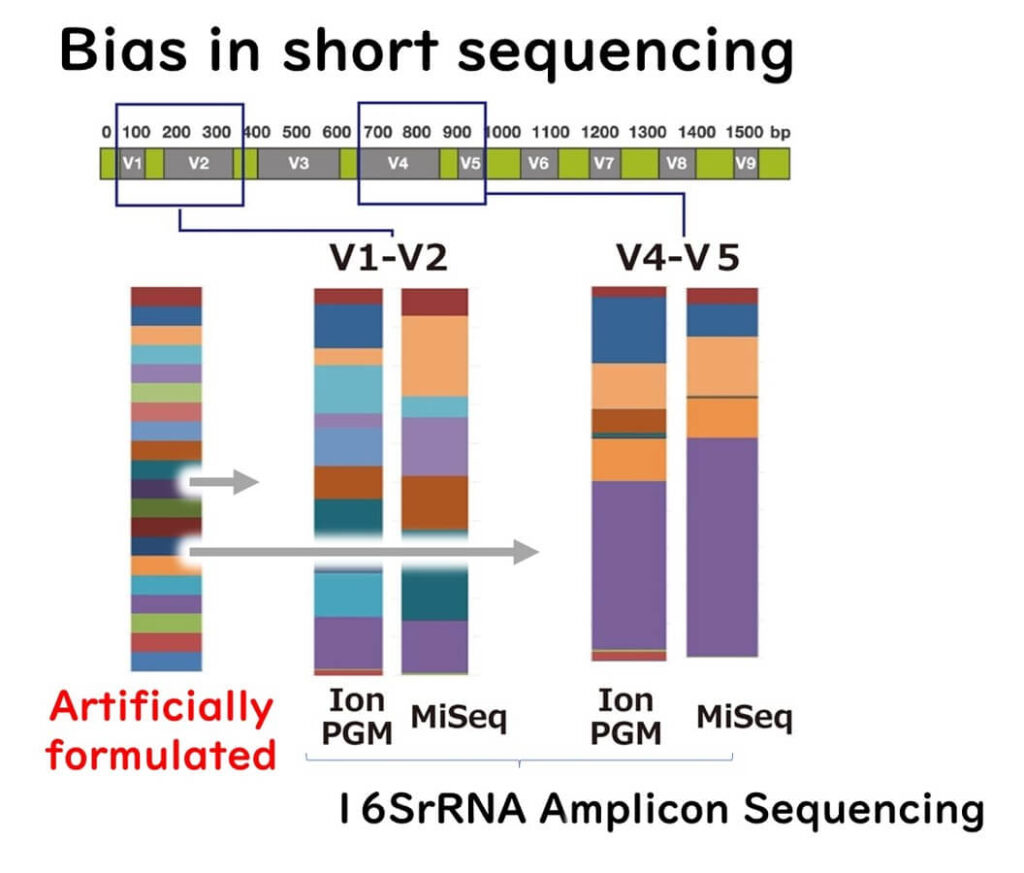

Limitations of 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing: Short-Read Bias and Taxonomic Resolution

For the past three decades, microbial isolates have been identified using full-length 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing via the Sanger method, allowing for high-accuracy taxonomic identification of isolated colonies.

However, 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing with next-generation sequencing (NGS) extracts and analyzes only partial sequences of 16S ribosomal DNA, typically used to infer operational taxonomic units (OTUs). While this approach is high-throughput and cost-effective, its limited sequence length introduces classification biases.

For a detailed explanation of OTUs, please see the article "Streamlined Molecular Methods for Microbial Identification: A Practical Guide"

NGS technologies primarily generate short-read sequences, typically 300 to 500 bases long. As a result, 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing cannot reconstruct full-length 16S ribosomal DNA, leading to lower resolution in taxonomic classification compared to Sanger sequencing.

For more on the basics of short-read sequencing in next-generation sequencers, please refer to the article "DNA Sequencing in Food Microbiology: Principles and Applications"

Since OTUs are based on partial sequences, identifying bacteria at the species level is challenging. Identification typically remains at the genus or family level. Even when a species-level identification is made, it is only an estimate of the closest species group.

Bias Due to Variable Regions and Primer Selection

Additionally, different target regions in the 16S ribosomal DNA sequence yield varying results. Studies using mock bacterial communities have demonstrated that primer selection significantly influences detected bacterial genera and species.

For example, using different primer pairs (V4-V5 vs. V1-V2) in sequencing can lead to variation in the microbial community profile, introducing bias in species identification.

上の図は下記論文のデータを抽出し、このブログの著者が整理し直したものです。

Fouhy, F. et al.,.16SrRNAgenesequencing of mock microbial populations-impact of DNA extraction method, primer choice and sequencing platform. BMC Microbiol. 16:123 (2016)

Currently, there is no scientific consensus on which variable region is best for accurate species-level identification. Compared to full-length 16S ribosomal DNA sequences, variable regions have lower resolution for species determination, and results can vary between regions.

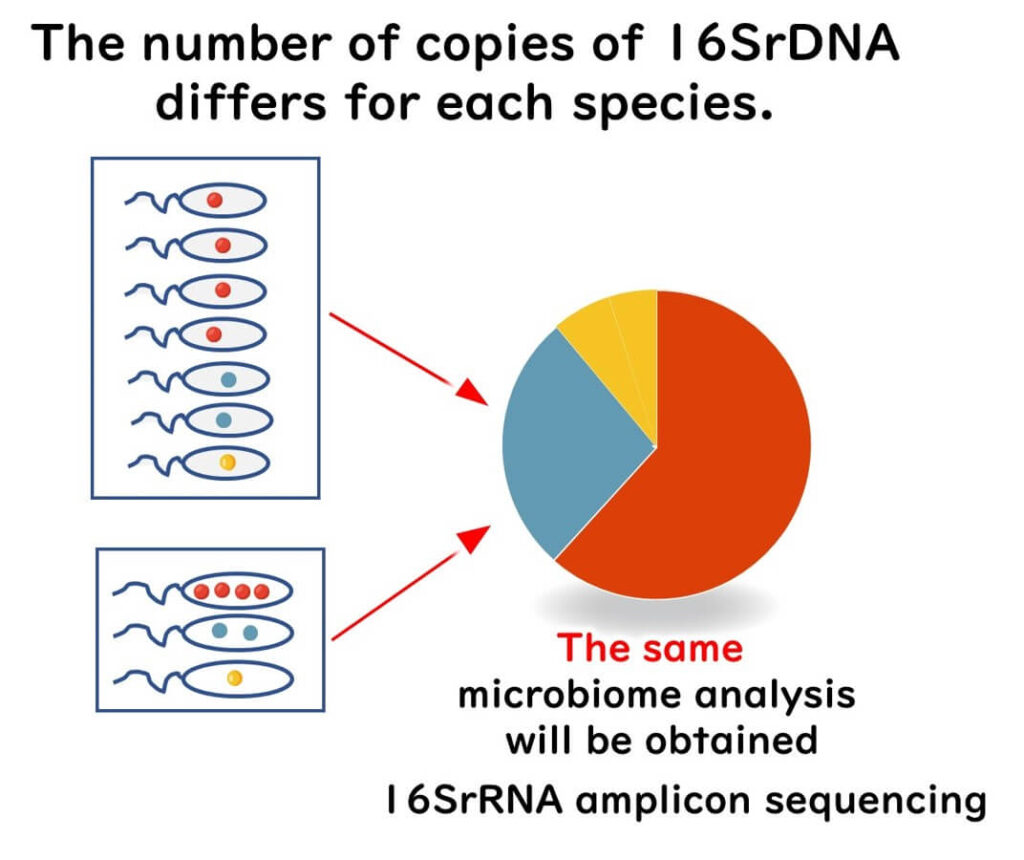

Impact of 16SrRNA Gene Copy Number Variability on Microbial Community Analysis

One significant source of bias in 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is the variability in 16S rRNA gene copy numbers among bacterial species. The number of copies per genome can range from 1 to 15, depending on the species (e.g., 1 copy in Erythrobacter litoralis and 15 copies in Photobacterium profundum).

As a result, the relative abundance of 16SrRNA genes in sequencing data does not directly reflect the actual number of bacterial cells in a sample. Instead, it is influenced by both bacterial population size and gene copy number variation, which can lead to over- or underrepresentation of certain taxa.

Despite this limitation, many studies assume that 16SrRNA gene abundance is directly proportional to bacterial cell abundance. However, this assumption oversimplifies microbial community analysis and can introduce significant errors in population estimates.

To ensure accurate interpretation of sequencing results, it is crucial to account for gene copy number variability when analyzing bacterial community composition.

For example, consider a microbial community consisting of four bacterial species (A, B, C, and D). If each species contained one 16S rRNA gene copy per genome, their relative abundance in sequencing data would reflect their true population sizes.

However, if species A had 4 copies, species B had 2 copies, and species C had only 1 copy, their representation in sequencing results would be skewed, making species with higher gene copy numbers appear more abundant than they actually are.

To minimize this bias, researchers should consider gene copy number normalization strategies when interpreting bacterial community structure.

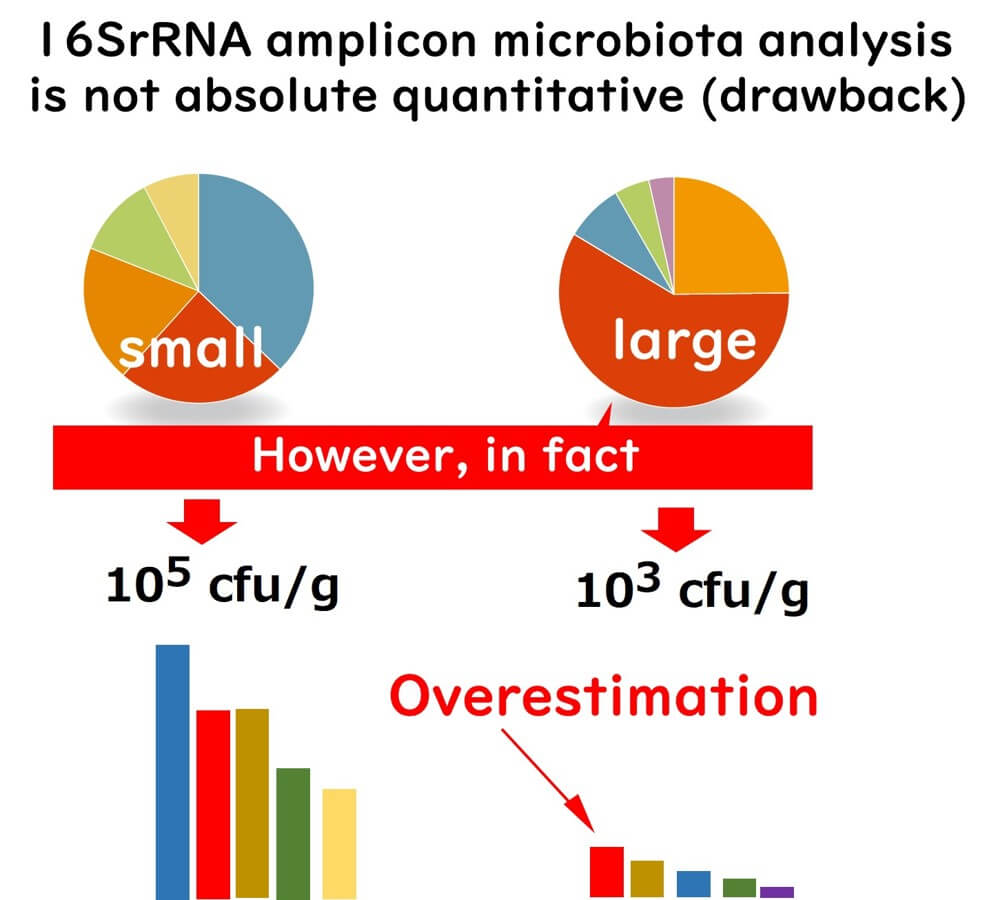

Limitations of 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing: Relative Abundance vs. Absolute Quantification

One critical limitation of 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is that it does not provide absolute microbial quantification. Instead, it measures relative abundance, which can sometimes misrepresent microbial population dynamics.

For example, consider two samples:

- Sample A: 10⁵ cfu/g total bacteria

- Sample B: 10³ cfu/g total bacteria

Despite its higher absolute abundance, Pseudomonas in Sample A may appear less dominant than in Sample B, where Pseudomonas is overrepresented due to the lower overall bacterial load.

Ignoring absolute bacterial counts when interpreting sequencing results can lead to incorrect conclusions about the metabolic activity and ecological significance of specific microbial taxa.

Practical Considerations for Microbial Community Analysis

TTo ensure accurate interpretation of microbial community data, it is essential to consider both absolute and relative abundance.

Researchers should supplement 16SrRNA sequencing data with quantitative methods (e.g., qPCR or culture-based enumeration) to gain a more complete picture of microbial populations.

Sources of Bias in 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing: Protocols, Primers, and DNA Extraction Methods

Bias in 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing is not limited to targeted regions—it also arises from differences in sequencing protocols 1), primer selection2), and DNA extraction methods3).

For example, results obtained using MiSeq vs. Ion PGM can vary significantly due to differences in sequencing chemistry and data processing pipelines. Similarly, even when targeting the same 16S rRNA gene region, the choice of primers can lead to variation in detected bacterial taxa.

To ensure comparability of sequencing data, it is essential to standardize primer selection and avoid switching primers arbitrarily when analyzing microbial communities across samples. Additionally, variations in DNA extraction kits can further contribute to differences in sequencing results, making protocol consistency a key factor in microbial community analysis.

Studies indicate that comparing microbial sequencing results across different protocols is analogous to comparing "apples and oranges"4)—the data may appear similar but originate from fundamentally different methodologies.

This discrepancy arises because sequencing platforms and protocols use distinct workflows, including variations in DNA library preparation, amplification efficiency, and bioinformatics pipelines. Consequently, results generated using different sequencing methods may not be directly comparable.

Standardization for Reliable Microbial Community Analysis

Currently, there is no globally standardized protocol for 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing, making cross-study comparisons challenging.

To improve reproducibility and data reliability, laboratories should establish internal standard operating procedures (SOPs) that define consistent sequencing regions, primer sets, and DNA extraction methods. Maintaining protocol uniformity within a research group or organization ensures more accurate comparisons of microbial community data.

Practical Implementation of 16SrRNA Amplicon Sequencing: Start Using It Today

To successfully implement 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing, it is essential to set clear objectives and apply the method to achieve practical goals.

Academic research often strives for perfection, making its methodologies appear complex and overly ambitious. However, in the food industry, waiting for perfect results may lead to missed opportunities to utilize the technology. In many cases, speed and practical insights are more valuable than absolute precision.

Keeping this in mind, it is beneficial to integrate 16SrRNA sequencing into routine microbial monitoring and food safety assessments, rather than delaying its adoption for the sake of unattainable perfection.

Each facility in the food industry can establish its own objectives for utilizing 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing. The best approach is to start using it and refine methodologies through trial and error.

- Standardize experimental conditions and sequencing protocols within your company to ensure data consistency.

- Acknowledge the limitations of OTU-based classification, recognizing that results are influenced by the presence of live and dead bacteria.

- Define practical applications for microbial monitoring, contamination tracing, or food safety validation.

- Encourage innovation by continuously testing and refining sequencing strategies in real-world conditions.

By integrating 16SrRNA amplicon sequencing into routine workflows, companies can generate valuable insights and develop novel approaches for microbial community analysis.