There are no specific protocols provided by ISO standards for environmental monitoring in food manufacturing plants. However, having concrete protocols is convenient when conducting monitoring in the field. In 2012, EU experts worked on establishing a unified protocol, particularly for the important bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. This article provides a digest of this protocol, focusing on key points with illustrations for clarity. While the focus is on Listeria, the fundamental methods of microbial sampling in food factories are also covered, making this a valuable read for beginners in food microbiology.

Reference:

ANSES, France

Guidelines on sampling the food processing area and equipment for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes, Version 3 – 20/08/2012

It is strongly recommended that this article be read in conjunction with the following blog entry, which provides an introduction to environmental monitoring in food factories:

The Importance of Environmental Monitoring in Food Factory Hygiene Management

Background to the creation of the protocol

International Situation of Mandatory Environmental Monitoring

First, let us clarify the international legal status of environmental monitoring.

The European Regulation (Commission Regulation (EC) 2073/2005) mandates that food business operators, especially those handling ready-to-eat (RTE) foods—foods consumed without further cooking—conduct microbial testing for Listeria monocytogenes on equipment and throughout the product's shelf life.

In North America, environmental monitoring for Listeria monocytogenes in RTE food manufacturing facilities is recommended but not legally mandated by the FDA. Guidance documents advise that RTE food manufacturers take environmental samples to verify the effectiveness of sanitation programmes and process controls, though this is not a legal obligation.

In other regions, such as Brazil, Japan, China, and South Korea, testing for L. monocytogenes in final products and processing environments is generally not required by law. Instead, testing for indicator organisms or Listeria spp. is used as part of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP).

Therefore, the legal status of Listeria environmental monitoring varies significantly by region, depending on local regulations.

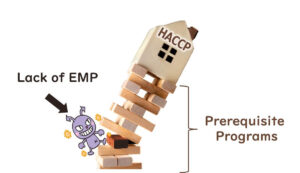

Lack of Unified International Protocols

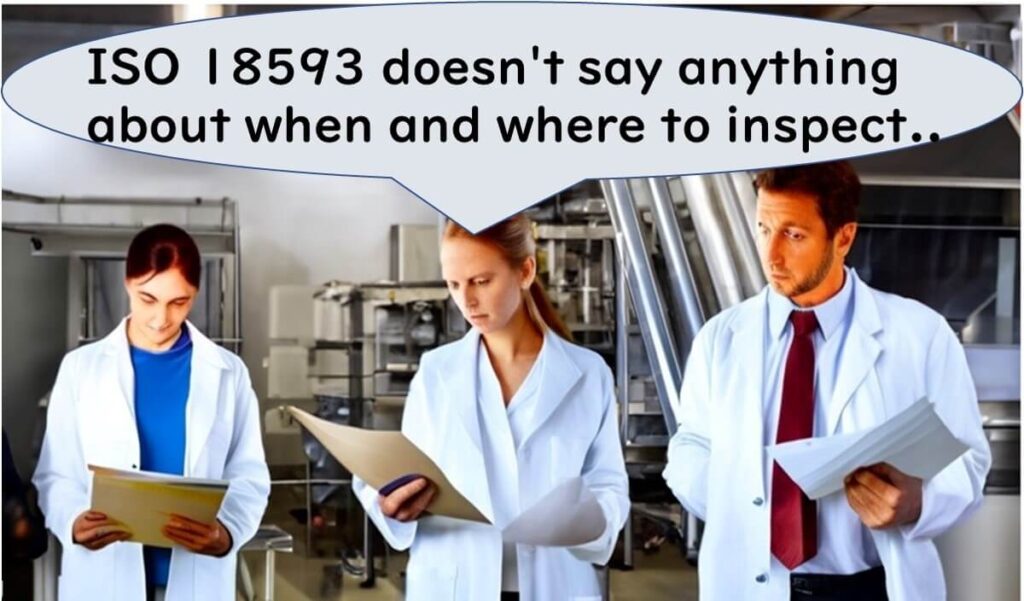

There is an international standard—ISO 18593—that describes surface sampling methods for the detection or enumeration of bacteria in food processing areas and equipment. However, it does not provide specific protocols for detecting Listeria. In particular, the ISO standard lacks detail on:

- When sampling should be conducted.

- Which areas should be sampled.

As a result, there was a need for specific guidelines to help quality managers in food manufacturing plants monitor Listeria contamination effectively.

A large-scale survey conducted in 2010 on surface sampling practices (with responses from 137 individuals across 15 EU countries, including food business operators, hygiene service providers, and public control services) revealed that sampling was often performed incorrectly. Such errors increase the risk of missing Listeria during monitoring.

In response, in 2012, the European Union Reference Laboratory for Listeria monocytogenes formed a working group to develop comprehensive guidance documents. The group included 20 members from seven EU countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, Denmark, Ireland, and Estonia), three National Reference Laboratories (NRLs), and other organisations.

By standardising protocols, the aim was to ensure effective and reliable environmental monitoring for Listeria monocytogenes in food manufacturing environments. This article summarises those guidelines, providing both newcomers and experienced professionals with essential knowledge on microbial sampling and contamination control.

Purpose and Overview of the Protocol

Purpose

The objectives of this unified protocol are:

- To provide a specific environmental monitoring protocol focused on Listeria monocytogenes.

- To specify the locations, methods, and timing for swab sampling to detect L. monocytogenes on surfaces in RTE food processing areas and equipment.

Excluded Topics

Despite its importance, this protocol does not cover the following areas:

- Quantification of Bacteria: Swab testing does not capture all bacterial cells, and recovery rates are variable and unknown. Therefore, the protocol only addresses detection.

- Other Sampling Locations: Techniques for sampling processing aids such as compressed air, brine, and wastewater are not included.

- Sampling Frequency and Rotation: The optimal frequency and selection of sampling points must be tailored to each factory. No specific advice is provided here.

- Evaluation of Cleaning and Disinfection Efficiency: This document is not intended for assessing sanitation effectiveness.

Sampling Locations

Here is a non-exhaustive list of locations recommended for microbial sampling:

- Non-food contact surfaces: drains, floors, standing water, cleaning tools, washing areas, floor scales, hoses, hollow rollers, conveyors, equipment frames, internal panels, condensate drip pans, forklifts, hand trucks, carts, trash bins, freezers, ice makers, cooling fins, aprons, ceilings, walls, cold surfaces, insulation around cooling units, door seals, vacuum cleaner contents, door handles, and taps.

- Food contact surfaces: conveyor belts, slicers, cutting boards, dicers, hoppers, shredders, blenders, peelers, collators, packaging machines, containers, and reusable gloves.

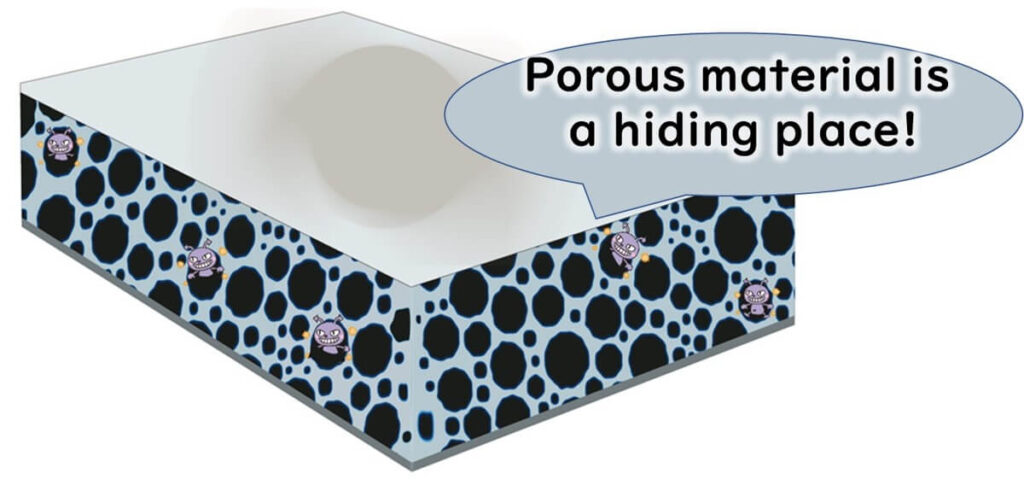

Special attention should be paid to hard-to-clean areas, including surfaces that are fibrous, porous, or rusty, hollow materials with gaps, and inaccessible parts of equipment.

Sampling such hidden spots, where food residues accumulate, may require equipment disassembly with the maintenance team's cooperation.

Frequent sampling should be conducted where food is exposed to contamination. Occasional sampling in less critical zones, such as raw material storage, is also advisable.

Sampling Timing

Timing During the Day

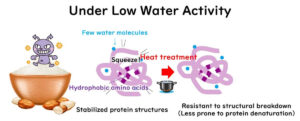

To detect Listeria biofilms, avoid sampling immediately after cleaning and disinfection. Reasons include:

- False Negatives: Damaged but viable cells may not grow on culture media.

- Increased Detectability During Processing: Vibration and food contact may dislodge bacteria from biofilms, making detection easier.

That said, post-cleaning swabs can indicate failure if Listeria is found. However, negative results should not provide false reassurance.

To maximise detection, sampling should be conducted during processing—at least two hours after production starts or at the end of the process, before cleaning begins.

Note: While Zone 1 surfaces (direct food contact) are typically excluded from routine pathogen testing, the European approach includes them. European regulations tolerate Listeria at ≤100 cfu/g, enabling a more flexible response. Thus, Zone 1 is monitored. In contrast, North American practices focus on Zones 2–4, only sampling Zone 1 if issues arise elsewhere.

If Listeria is found during processing, test raw materials in parallel to distinguish whether the contamination source is internal or external.

Timing During the Week

If sampling is not done daily, avoid always sampling on the same weekday. High-risk events—maintenance, construction, or increased output—can occur on specific days. Varying the schedule improves contamination risk assessment.

Sampling Equipment

Swab Sticks

Swab sticks with sterile cotton or synthetic tips, packed in sterile tubes, are standard. For some surfaces, cotton residue may cause internal contamination.

Swabs are ideal for small or difficult areas. Compared to rigid cotton types, these absorb more and can be scrubbed harder. Use:

- Dry swabs for wet surfaces

- Moistened swabs for dry surfaces

Only moisten the tip without dripping. After sampling, return swab to its tube to maintain sterility.

Sponges, Cloths, and Gauze Pads

Sterilised and individually packaged, these tools suit larger areas. Ensure they are free of inhibitory substances. If moistening is needed, avoid over-saturation to prevent dripping.

Diluent

Diluents for moistening include:

- 1 g/L peptone solution

- Peptone physiological saline

- One-quarter strength Ringer’s solution

Sterilise by autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes. Do not use phosphate-buffered diluents or enrichment broths (e.g. Fraser) as these can interfere with detection or encourage environmental growth of Listeria.

For post-cleaning sampling, use neutralising diluents. Avoid these if not required, as they may stress cells.

Other Equipment

- Disposable sterile gloves (optional)

- Cool box (1–8°C) for sample transport

- Sterile absorbent paper for wet areas

- Mixer or peristaltic homogeniser

Sampling

Sampling Area

To improve detection, sample 1000–3000 cm² (0.1–0.3 m²) in flat areas like conveyors.

Avoid using templates or rulers—they may transfer contaminants.

Instead, use body-based references: middle finger to elbow (~45 cm) or spread hand (~20 cm).

Consistent area sizes improve long-term trend analysis.

Procedure

Swab Sticks: Rotate swab in small areas. Return to the tube without contaminating the tip. Clean the area post-sampling with alcohol wipes.

Sponges/Cloths: For wet surfaces, first remove standing water using sterile paper. Handle sampling materials aseptically with gloves or via their sterile packaging.

Count all tools before and after to avoid leaving items behind.

Transport and Storage of Samples

Transport samples at 1–8°C using a cool box. Store at 3°C ± 2°C if necessary. Follow EN ISO 7218 guidelines: test within 24 hours of lab arrival, and no later than 36 hours post-sampling. Record the time elapsed between sampling and analysis.

Analysis of Samples

Swab Sticks

Add ≥9 ml of Half Fraser Broth (EN ISO 11290-1) to the swab tube. Mix for 30 seconds. Detect L. monocytogenes using EN ISO 11290-1 or a validated alternative method.

Sponges/Cloths/Gauze Pads

Add broth (9× pre-moistened weight) into the bag. Mix using a peristaltic homogeniser for 1 minute. Proceed with detection as above.

Note: EN ISO 11290-1 includes enrichment, differential plating, and biochemical testing.

Interpretation of Results and Corrective Actions

If Listeria is detected, establish acceptable limits for food and non-food contact surfaces within your HACCP plan. If results exceed those limits, implement corrective actions as outlined in your HACCP procedures.

It is highly recommended to read this article alongside the introductory piece on this blog:

The Importance of Environmental Monitoring in Food Factory Hygiene Management