Campylobacter food poisoning is widely associated with chicken, especially undercooked poultry dishes. This belief is commonly held. However, Campylobacter is not limited to chickens raised on poultry farms. It can also be found in the intestines of cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats, as well as wild animals and birds. This indicates that various meats within the food supply chain could potentially serve as infection sources.

So, what proportion of Campylobacter foodborne infections can truly be attributed to chicken meat? In this article, I introduce a study that examines this question using molecular epidemiological methods.

Sheppard et al.

Campylobacter genotyping to determine the source of human infection

Clinical Infectious Diseases 2009; 48:1072–8

Most Cases of Campylobacter Enteritis Are Sporadic

First, let us consider the typical nature of Campylobacter enteritis. The vast majority of Campylobacter foodborne infections are sporadic, involving only a few individuals per case. Unlike large outbreaks, identifying the transmission route in such sporadic cases is extremely difficult.

With Campylobacter in particular, most causative foods remain unidentified due to the following reasons:

- A relatively long incubation period

- Mild symptoms that may go unnoticed

- Rapid die-off of the bacteria in food

Incidence of Campylobacter Infection from Sources Other Than Chicken

Campylobacter lives in the intestines of many animals—including wild birds, cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats—in addition to poultry. Therefore, it is plausible that sources other than chicken meat may also cause infection.

To explore this, Dr Sheppard and colleagues at the University of Oxford conducted a comprehensive study to statistically infer likely infection sources based on genotyping data.

Summary of their methodology:

- Between July 2005 and September 2006, they conducted Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) on 5,674 Campylobacter strains isolated from human Campylobacteriosis cases in Scotland, along with 999 clinical strains from suspected cases.

- They then used source attribution analysis to examine the relationship between sequence types (STs) and their probable origins.

Note: For a more detailed explanation of MLST analysis, please see the related blog article:

Bacterial Strain Typing: PFGE, MLST, and MLVA in Molecular Epidemiology

Two analytical models were used, but the technical specifics are omitted here. The main results were as follows:

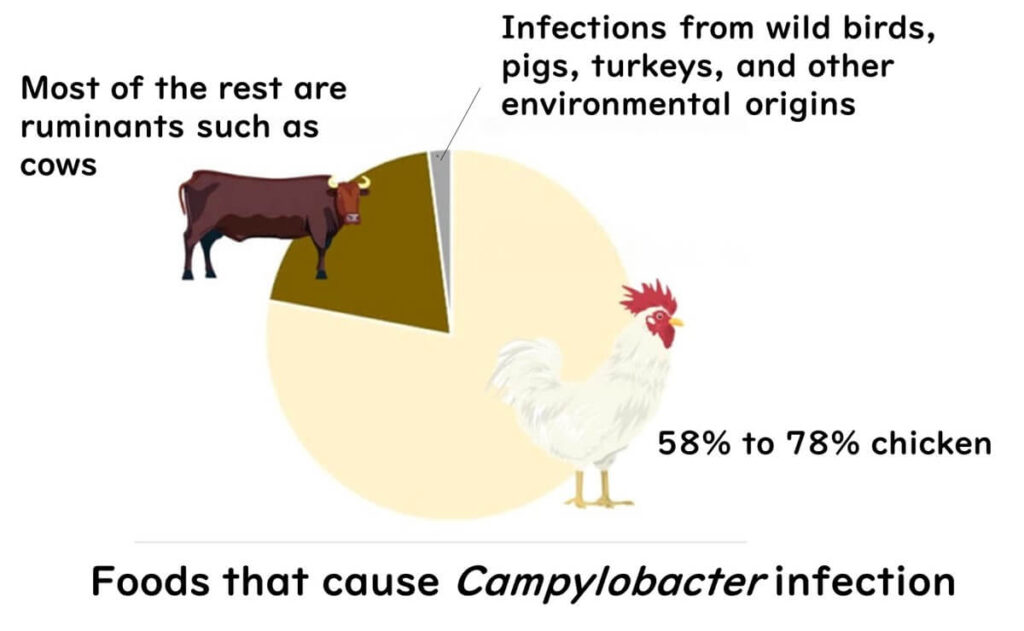

- It was estimated that 58% to 78% of the analysed Campylobacter jejuni strains were primarily transmitted via chicken meat (the variation reflects the different models used).

- Among infections not attributed to chicken, most were linked to ruminant animals—especially cattle.

- Campylobacter strains from wild birds, pigs, turkeys, and environmental sources were relatively rare in human clinical isolates.

My Take on This Study

From my perspective, the key takeaway is the robust statistical confirmation that chicken meat remains the dominant source of Campylobacter infection. What struck me most is that while other animals do carry Campylobacter, their relative contribution to human disease appears marginal—at least in developed countries with high poultry consumption and robust surveillance systems.

This has significant implications for food safety practice. For quality assurance professionals, it reinforces that the poultry industry must remain the primary focus of control measures. Effective intervention at the farm, slaughterhouse, and retail level—especially in preventing cross-contamination and maintaining cold chain integrity—should be prioritised in any Campylobacter risk management strategy.

This aligns with what I have seen throughout my years in the food sector: while it's essential to consider multiple potential sources, the overwhelming majority of preventable cases still originate from poultry. This study confirms the critical importance of targeted control within the poultry supply chain.

If you would like to revisit the fundamentals of Campylobacter, please see the following article:

Understanding Campylobacter: Food Poisoning Risks and Prevention Tips