Clostridium perfringens, commonly referred to as the "cafeteria germ," is a key cause of large-scale food poisoning outbreaks, particularly in high-volume meal preparation settings. This bacterium thrives in warm, oxygen-free environments, often found in slow-cooling dishes like stews and curries. In this article, we explore the unique traits of C. perfringens, its role in foodborne illness, and critical steps for preventing contamination to ensure food safety in catering facilities, cafeterias, and restaurants.

Understanding Clostridium perfringens: Key Traits and Survival Mechanisms

Before exploring the details of Clostridium perfringens, we recommend reviewing our introductory article on Gram staining and microbial properties. This foundational knowledge will enhance your understanding of the unique characteristics of this bacterium and its role in food microbiology.

Gram Staining and Microbial Properties: A Comprehensive Overview

Where Does It Live?

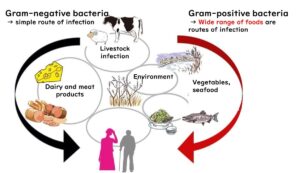

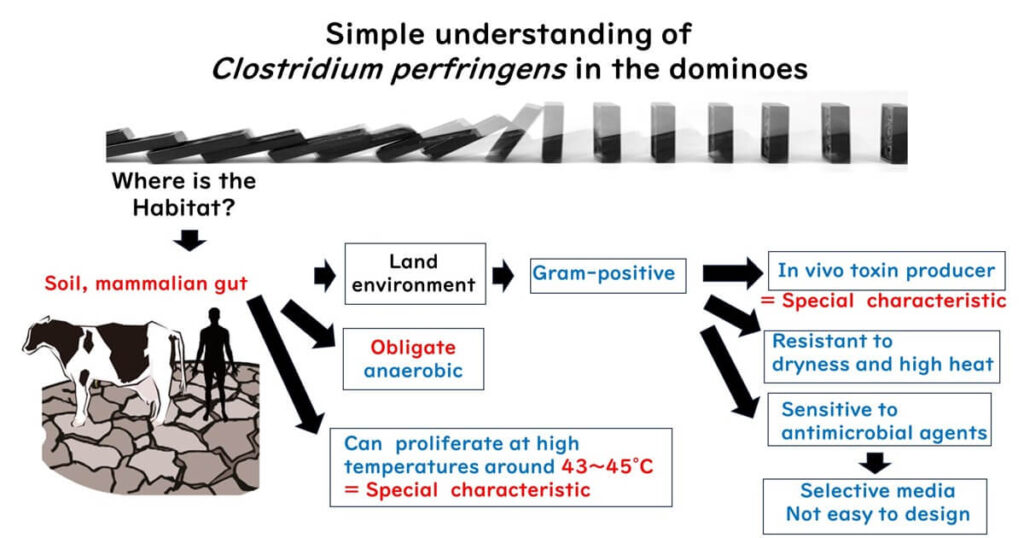

C. perfringens thrives in diverse environments, primarily in soil and the intestines of mammals like humans and cows. This adaptability makes it a persistent presence in both natural and human-influenced ecosystems.

What Kind of Bacterium Is It?

This Gram-positive bacterium is classified as an in vivo toxin producer, which means it doesn’t fit neatly into the typical categories of infection-type or toxin-type bacteria. It’s something in between, releasing toxins inside the host.

Ideal Growth Conditions:

C. perfringens grows best at a warm 43–45°C, conditions often found in improperly cooled bulk-prepared foods.

Survival Skills:

Heat-Resistant Spores

Like other members of the Clostridium genus, it forms spores that can withstand high temperatures, ensuring survival during cooking processes.

Oxygen-Free Growth

As an obligate anaerobe, it only grows in environments devoid of oxygen, such as the interiors of improperly cooled stews or curries.

Acid Sensitivity

While it is tough in many conditions, it struggles in highly acidic environments.

Resistance to Antibiotics:

Once C. perfringens forms spores, it becomes resistant to most antibiotics, making it particularly hard to eliminate.

Laboratory Cultivation:

Selective media for C. perfringens leverage its anaerobic nature and spore-forming ability, much like the methods used for Clostridium botulinum.

Understanding these traits one step at a time provides a comprehensive view of why C. perfringens is such a resilient and challenging bacterium in food safety.

Common Patterns of Food Poisoning by Clostridium perfringens

C. perfringens thrives in diverse environments, from soil to the intestines of animals, making it a common contaminant in food. This bacterium often hitchhikes on root vegetables pulled from the soil, inadvertently turning them into sources of food contamination.

Vulnerable Dishes

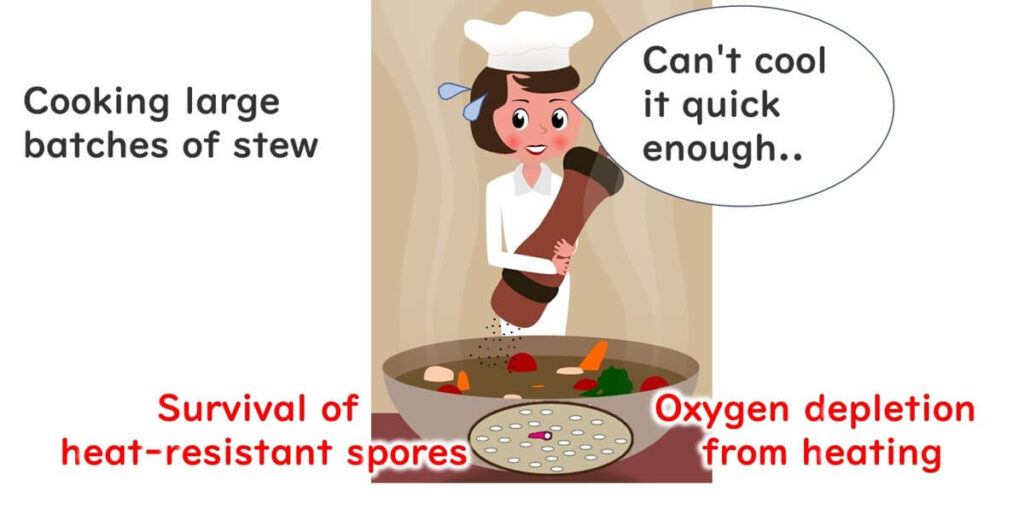

Dishes like curry rice and stews are frequent targets for C. perfringens contamination, particularly during the cooling process. Here's why:

Heat and Bacteria

High cooking temperatures destroy most bacteria but leave the heat-resistant spores of C. perfringens intact.

The Awakening of Spores

When exposed to high temperatures around 100°C, these spores "awaken" and become active.

The Perfect Breeding Ground

Warm post-cooking conditions provide an ideal environment for C. perfringens to multiply rapidly.

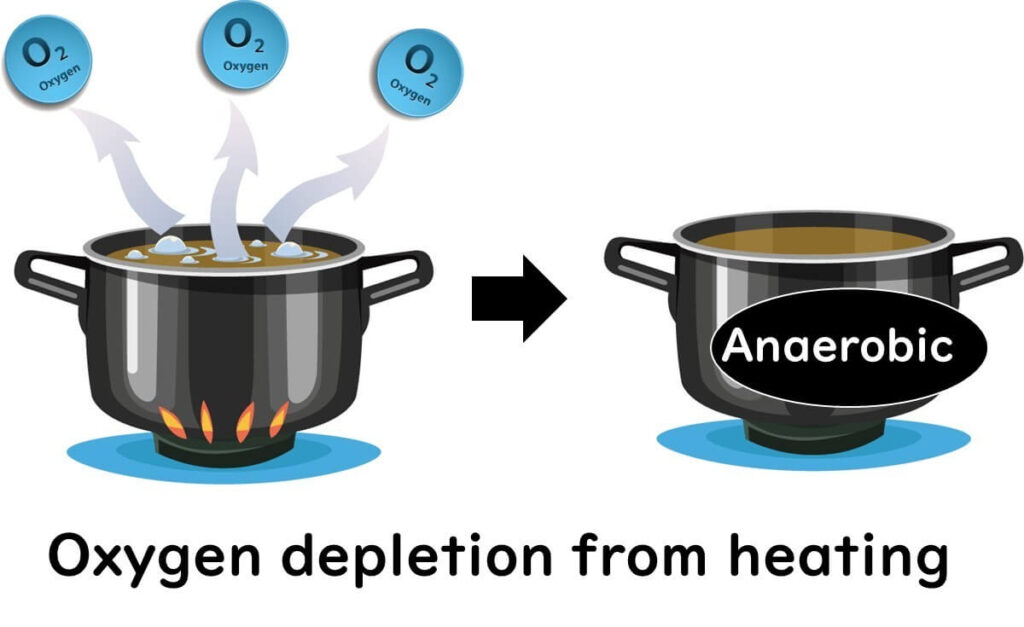

Anaerobic Conditions Post-Boiling

Boiling drives out dissolved gases from soups and stews, creating oxygen-free conditions perfect for bacterial growth (a phenomenon known as "degassing").

The Impact of Contaminated Food

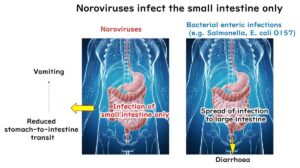

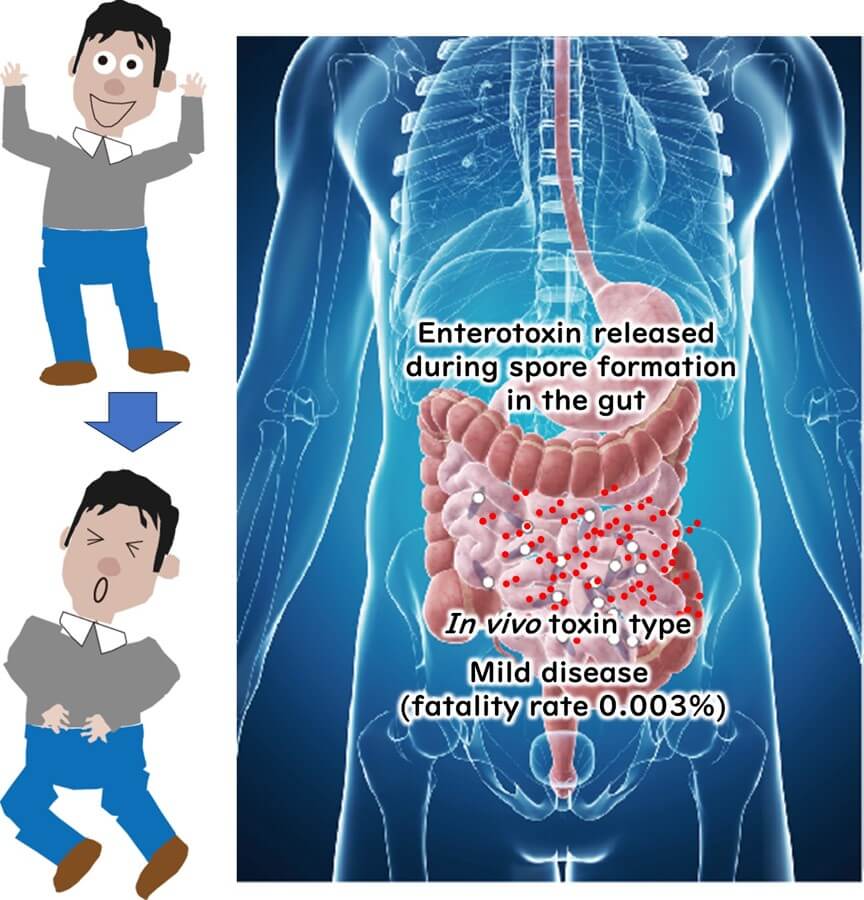

When food contaminated with C. perfringens is consumed, the bacteria enter the intestines and adapt to the environment by forming heat-resistant spores. During this transformation, the vegetative cells release enterotoxins, high-molecular-weight proteins that damage intestinal cells. This process leads to abdominal pain and diarrhea, the hallmarks of C. perfringens food poisoning.

Interestingly, the illness is not caused by the bacteria themselves but by the toxins they release during spore formation. This makes C. perfringens food poisoning a middle ground between infection-type and toxin-type foodborne illnesses.

Symptoms and Recovery

The average incubation period is about 10 hours, with common symptoms including abdominal pain and diarrhea. Vomiting and fever are less frequent. Fortunately, symptoms are typically mild and resolve within a day or two.

Prevention Tips

To minimize the risk of C. perfringens food poisoning:

Cool Food Quickly

Rapid cooling after cooking is essential. Place stews and curries in the refrigerator promptly to reduce the risk of bacterial growth.

Avoid Slow Cooling

Slow cooling creates conditions that encourage C. perfringens to thrive.

By following these precautions, you can ensure safer leftovers and prevent foodborne illness.

High-Risk Food Poisoning: C. perfringens and Large-Scale Outbreaks

The risk of large-scale food poisoning outbreaks is particularly high with Clostridium perfringens. This bacterium often becomes problematic in environments where meals are prepared in bulk, such as catering facilities, packed lunch businesses, and restaurants. Dishes like curries and stews, typically made in large quantities, are frequent sources of contamination.

Due to this pattern, C. perfringens outbreaks often result in a high number of affected individuals from a single incident. This characteristic has earned it the nickname "catering germ" or "cafeteria germ."

To mitigate the risks, bulk food preparation facilities must adhere to strict cooling practices and maintain proper hygiene during handling and storage.

C. perfringens: A Harmful Gut Bacterium and Its Role in Aging

C. perfringens is widely recognized as a harmful bacterium in the human gut. With age, the proportion of C. perfringens in the intestinal microbiota increases, while beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria decrease. This imbalance is associated with intestinal aging, decay, and even an increased risk of cancer.

The detrimental effects of C. perfringens stem from its ability to break down proteins and produce harmful substances such as ammonia, amines, phenols, and indoles. Some of these metabolic by-products, like nitrosamines, have carcinogenic potential.

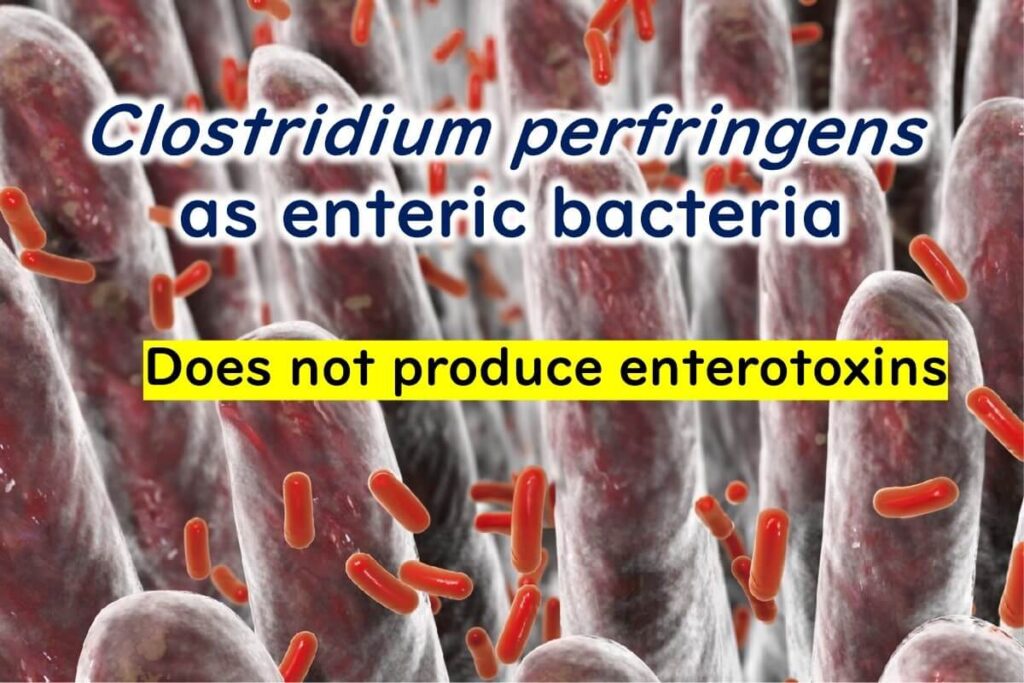

A decrease in Bifidobacteria combined with an increase in C. perfringens levels is considered an indicator of intestinal aging. However, naturally occurring C. perfringens in the human gut does not typically produce enterotoxins and is therefore not a direct cause of food poisoning under normal conditions.

The diarrheal form of C. perfringens, which releases enterotoxins when vegetative cells break down, is usually associated with contaminated food rather than gut-residing populations. While much remains unclear about its exact mechanisms, research continues to shed light on how C. perfringens contributes to both foodborne illnesses and broader health concerns.