In this article, aimed at beginners in the fields of food microbiology and microbiology, I will explain the relationship between foodborne pathogens, spoilage bacteria, and humans. From the perspective of utilizing stellar energy, both humans and microorganisms are considered losers compared to plants. This is because unlike plants, they cannot convert solar energy into chemical energy. From the viewpoint of extraterrestrials, plants may be the life forms worthy of respect, while humans and microorganisms might be seen as similar and inferior creatures. Therefore, food microbiology can be seen as a discipline that studies the battle between losers in terrestrial biology from an energy perspective.

This article introduces beginners to the intricate relationships between foodborne pathogens, spoilage bacteria, and humans. Unlike plants, which efficiently convert solar energy into chemical energy through photosynthesis, both humans and microorganisms lack this capability. From an extraterrestrial perspective, plants might be esteemed as superior life forms, while humans and microorganisms could be viewed as less advanced. Consequently, food microbiology emerges as a field that examines the interactions among these energy-limited organisms within Earth's biosphere.

Plants as Victors in Earth’s Ecosystem, Humans and Microbes as Secondary Players

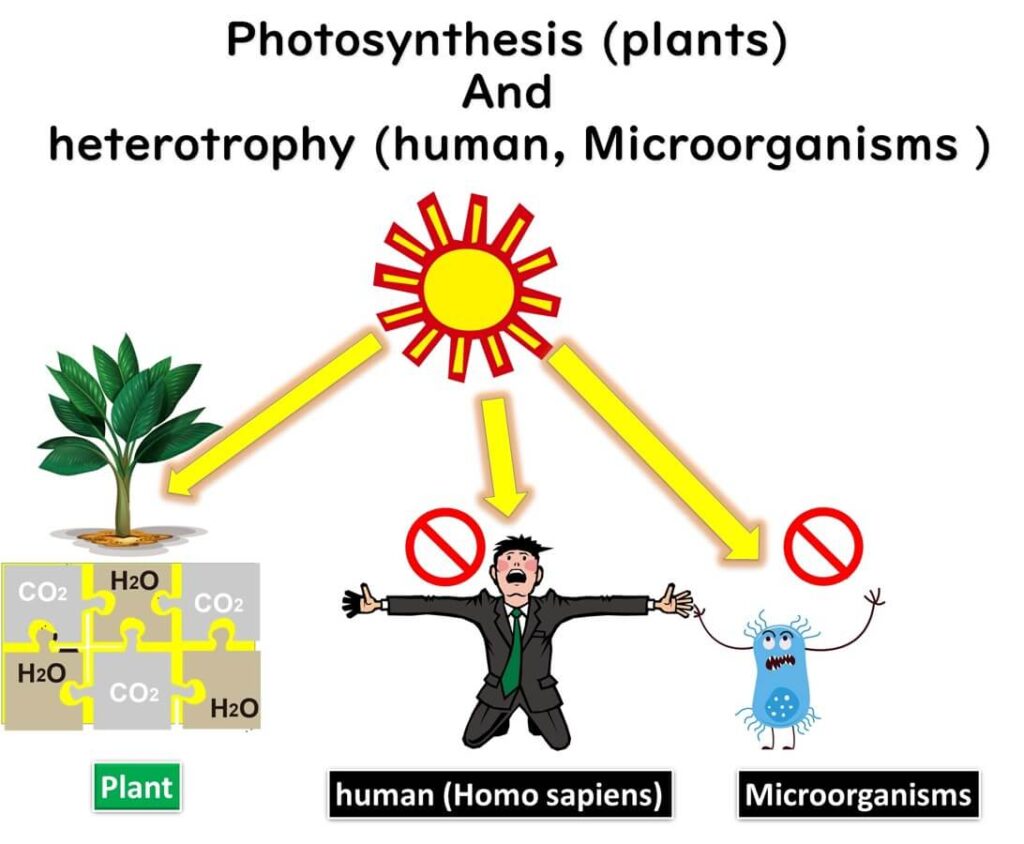

Among the diverse organisms living on planets orbiting stars, those that can directly utilise stellar energy hold a unique advantage. In our solar system, this ability is exclusive to organisms like plants, which can capture and transform sunlight into usable energy through a process called photosynthesis.

Plants harness solar energy to produce organic matter from simple compounds such as carbon dioxide and water. Imagine organic matter as a set of building blocks; solar energy acts like the adhesive holding these blocks together, a form of energy we know as chemical energy.

Conversely, animals — including humans — and microorganisms, such as those studied in food microbiology, have not evolved this ability to harness solar energy directly. Regardless of how much humans or microbes "reach out" towards the Sun, they cannot capture and store solar energy independently.

Note: phototrophic bacteria do exist on Earth as a whole but do not play a significant role in food microbiology

When comparing the capability of various life forms to utilise solar energy, plants emerge as clear "winners," while humans and microorganisms can be considered losers.

Considering this perspective, humans might assume that extraterrestrials are aware of our existence when visiting Earth. However, for beings focused on the independent fixation of solar energy, species like humans, who lack this capability, may hold little significance.

The true purpose of extraterrestrial attention might instead centre on analysing the remarkable solar energy fixation abilities of organisms such as plants.

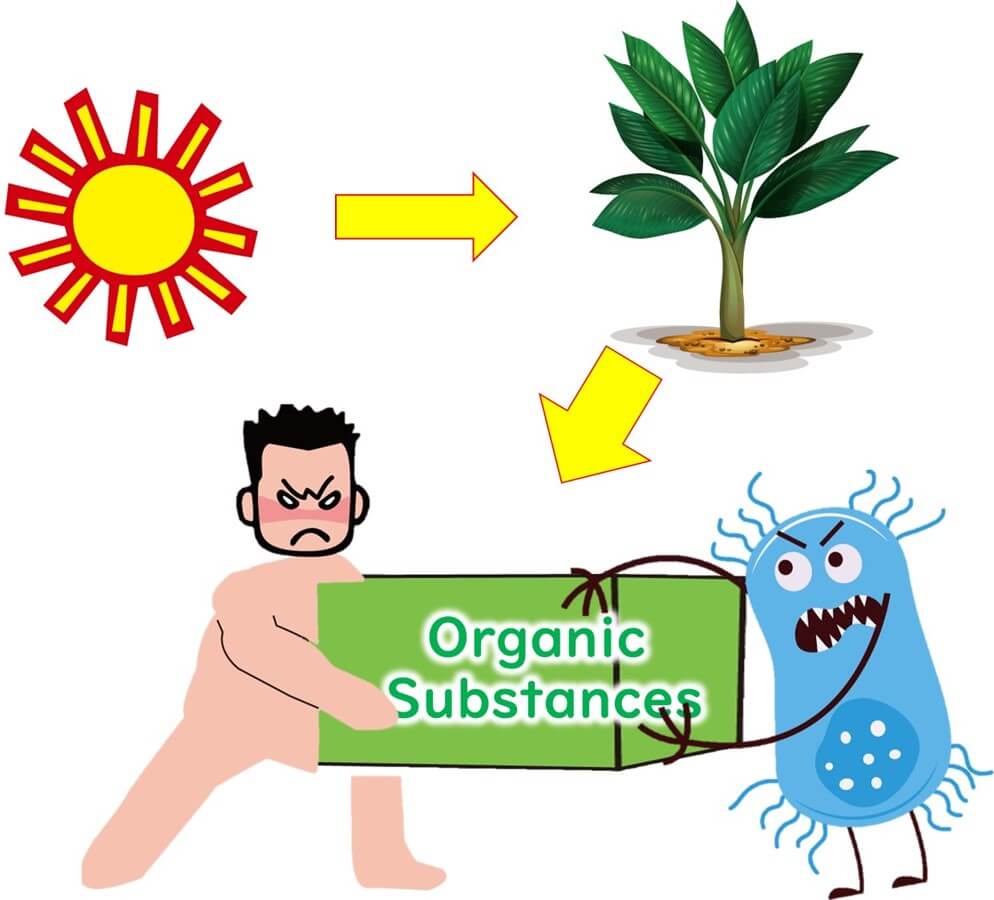

With this understanding of plants as energy 'winners' and humans and microbes as secondary players, we turn to examine the interactions between humans and microorganisms within the realm of food microbiology.

Humans and Microorganisms: Rivals in the Battle for Organic Matter Breakdown

As previously mentioned, both humans and microorganisms lack the ability to directly harness energy from the sun. As a result, their only option for obtaining energy is to break down plants.

This primitive and rather unfortunate lifestyle of destroying plant life stems from the inability to directly utilise solar energy.

Microorganisms, of course, share this same basic and unfortunate dependency.

In other words, within Earth's ecosystem, humans and microorganisms can be seen as rivals in a struggle between "losers," each competing for organic matter derived from plants.

With this understanding of the ecological roles of humans and microorganisms, let us delve deeper into the concept of decay within the field of food microbiology.

Decay Occurs When Microorganisms Outpace Us

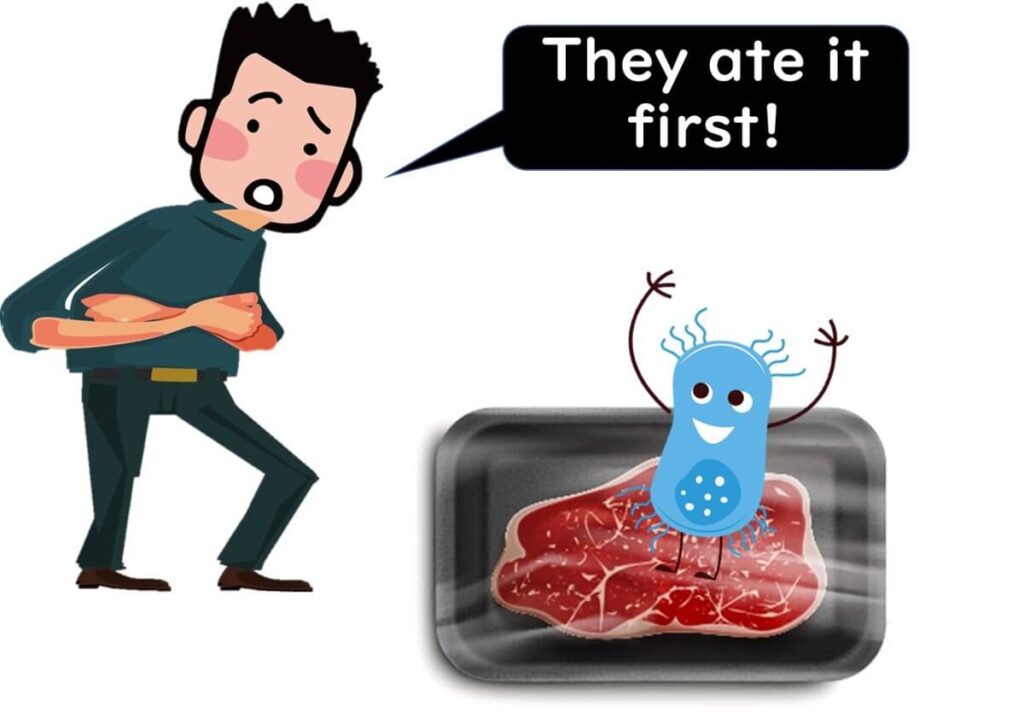

When humans consume organic matter derived from plants before microorganisms have had a chance to break it down, we consider it fresh food.

However, if microorganisms have already decomposed the organic matter before humans can consume it, we refer to this process as decay.

Since microorganisms have already begun breaking down the organic material, the level of chemical energy within it has diminished. Consequently, the byproducts of this microbial activity are often less palatable to humans.

In essence, decay happens when microorganisms have taken the lead in breaking down organic matter.

The purpose of emphasising this point is to clarify that the vast majority of microorganisms are simply competing with humans for resources, rather than posing a direct threat to them.

99.9% of Microorganisms Compete with Humans for Organic Matter, but They Don’t Attack

As previously mentioned, both microorganisms and humans are at a disadvantage in terms of harnessing energy within terrestrial biology. Microorganisms, for the most part, do not pose any significant threat to humans. Rather, humans may simply think, “Oops! The microorganisms got to the organic matter first!” when they observe microbial activity on food.

With this perspective, let's consider the following:

In any environment, exceptions exist. Among the majority of harmless microorganisms, there are rare cases where specific microbes may harm humans. Just as in the human world, where 99.9% of individuals are well-meaning, there are still a few ‘bad actors’. The microbial world is no different.

Note: The 99.9% figure is not a precise calculation based on the ratio of pathogenic bacteria to the total number of microbial species. Considering the vast population of microorganisms on Earth, the true figure is likely even closer to 100% than 99.9%.

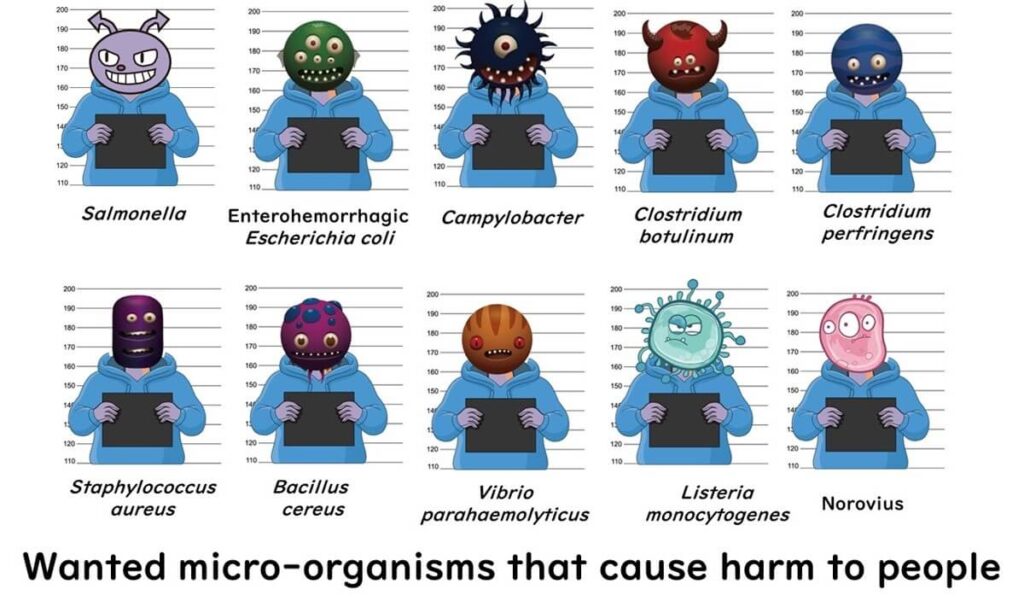

These microbial "fugitives" are akin to foodborne pathogens that we study in food microbiology.

It’s essential to recognise that while there are thousands or even millions of types of microorganisms, only a small fraction are classified as harmful ‘criminals’ that pose risks to humans.

When we encounter spoiled food, we tend to view it as dangerous.

Spoiled food contains a high concentration of microorganisms. If pathogenic bacteria are among them, their numbers may reach infectious levels. Therefore, it’s clear that consuming spoiled food is generally unwise.

However, for those studying food microbiology, it is crucial to understand that spoilage and the presence of foodborne pathogens are distinct concepts.

Some consumers believe that food past its expiration date is automatically unsafe. However, if no foodborne pathogens are present, such food will not necessarily cause illness. Conversely, even if food is within its expiration date, the presence of pathogens could still result in food poisoning.

In essence, food microbiology seeks to:

- Prevent being outpaced by the natural competition of microorganisms in consuming food.

- Prevent the contamination of food with microbial "fugitives" (foodborne pathogens).

While there are shared methods and strategies to achieve these objectives, food microbiology recognises the need to differentiate between general spoilage and pathogenic contamination.