This article explores Listeria monocytogenes, a resilient Gram-positive bacterium responsible for severe foodborne illness, particularly affecting pregnant women, the elderly, and those with weakened immune systems. Learn why this pathogen is a critical concern in ready-to-eat foods such as deli meats, cheeses, and smoked seafood. We delve into its unique survival abilities, its high fatality rate in outbreaks, and the regulatory differences across the U.S., EU, and Japan. Discover best practices and strategies to control this persistent threat in food production and safeguard public health.

Understanding Listeria monocytogenes: A Domino Effect of Adaptation

Before diving deeper, consider reviewing our foundational article on Gram staining and microbial characteristics. Understanding these basics will help contextualize the extraordinary survival strategies of Listeria monocytogenes, much like a domino effect where each piece of knowledge builds upon the last.

Gram Staining and Microbial Properties: A Comprehensive Overview

The Link Between Gram Staining and Microbial Properties

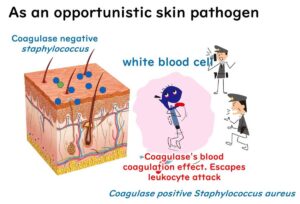

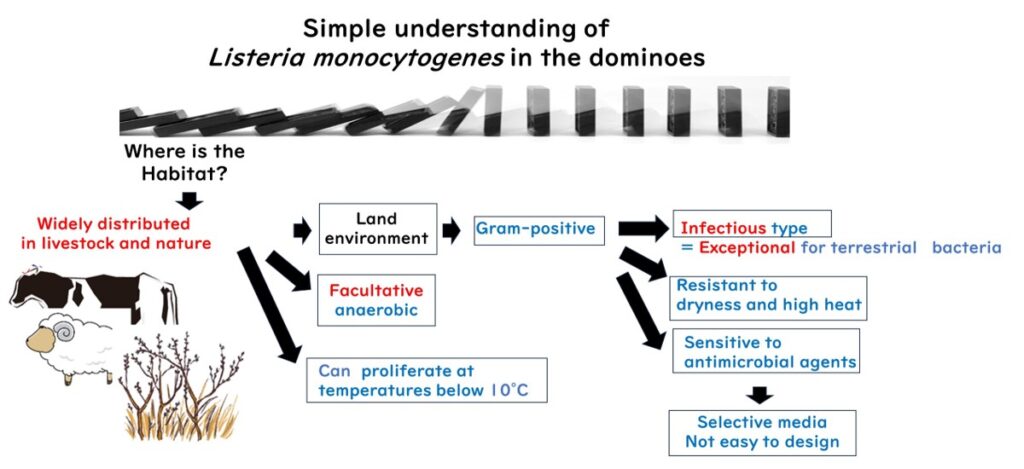

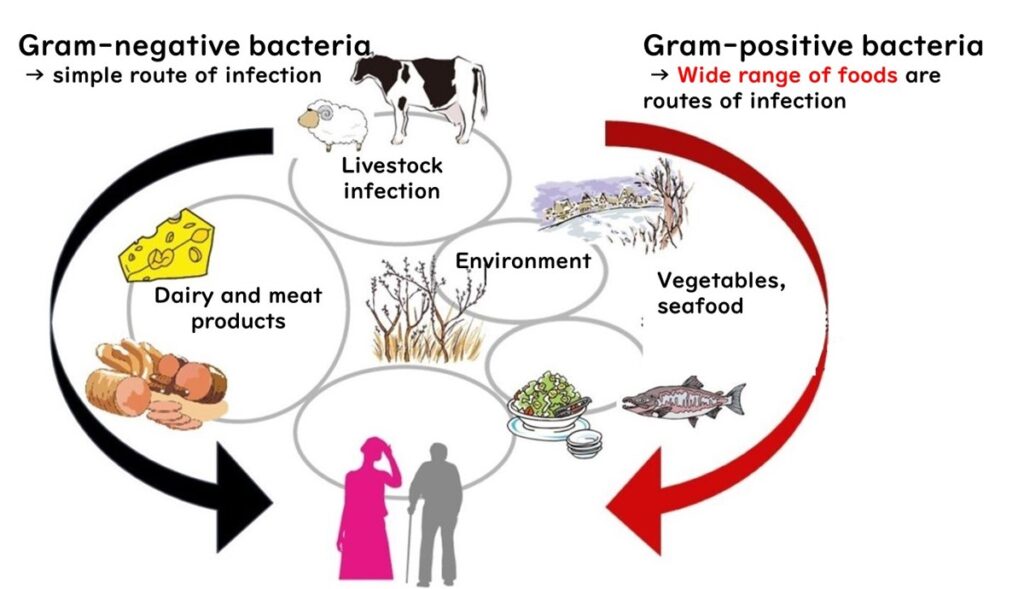

Listeria monocytogenes, a Gram-positive bacterium, is commonly found in the intestines of animals such as sheep, cows, and pigs. Originally recognized as a pathogen affecting livestock, it has since been identified as a significant threat to human health due to its remarkable adaptability.

Unlike many Gram-positive bacteria associated with toxin-based food poisoning, L. monocytogenes causes infection-based foodborne illness. This deviation from the norm makes it a unique player in the microbial world.

Temperature Resilience

Thriving at 37°C—typical of mammalian body temperature—L. monocytogenes can also grow in refrigeration temperatures, making it a persistent challenge in cold food storage. This adaptability sets it apart from most Gram-negative foodborne pathogens.

Resistance to Environmental Stress

As a Gram-positive bacterium, L. monocytogenes can withstand dryness, high salt concentrations, and other harsh conditions. These traits position it as one of the most resilient foodborne pathogens, capable of surviving where others cannot.

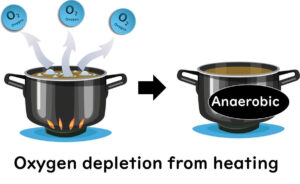

Facultative Anaerobe with Acid Tolerance

In addition to thriving in mammalian intestines, L. monocytogenes is a facultative anaerobe capable of producing organic acids and thriving in acidic environments, such as those mimicking vinegar conditions.

Vulnerability to Chemical Agents

However, its Gram-positive nature makes it less resistant to certain chemical agents with hydrophobic functional groups. This limitation complicates the development of selective culture media for L. monocytogenes, compared to Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli or Salmonella.

Understanding the characteristics of L. monocytogenes reveals a domino-like cascade of traits that collectively explain its resilience and adaptability in various environments.

The High Fatality Rate of Listeria monocytogenes Foodborne Illness

Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen known for its severe symptoms and exceptionally high fatality rate, making it one of the deadliest causes of foodborne illness globally.

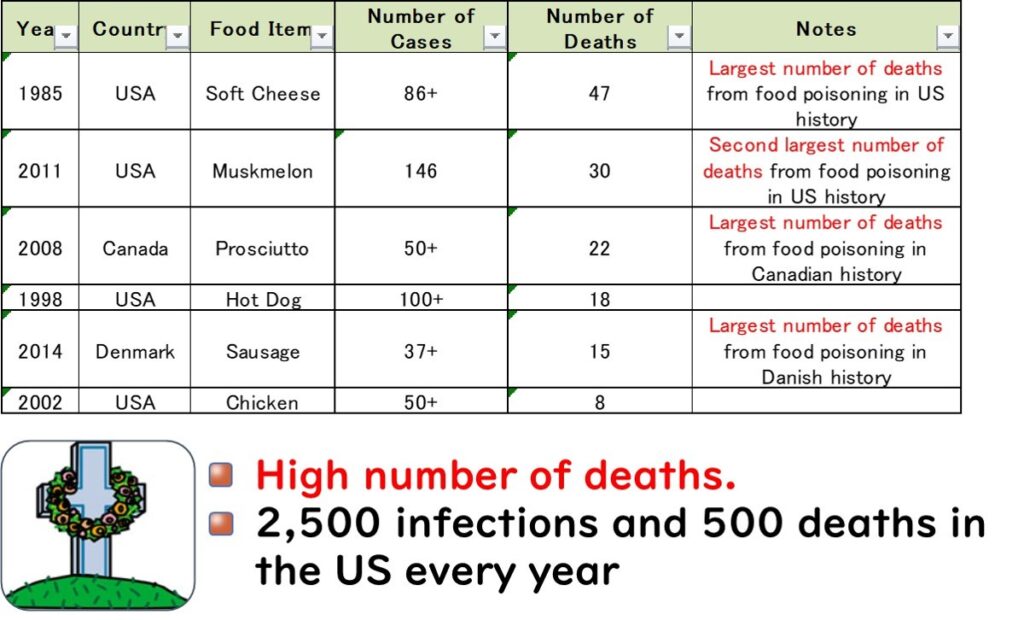

In several countries, L. monocytogenes has been responsible for the highest number of deaths in foodborne outbreaks. For instance:

- United States (1985): An outbreak linked to soft cheese caused 47 deaths, marking it as the deadliest foodborne illness incident in U.S. history.

- Canada (2008): An outbreak associated with deli meats led to 22 fatalities, the highest number of deaths from a single foodborne illness outbreak in Canadian history.

- Denmark (2014): An outbreak involving sausages resulted in 15 deaths, the most lethal foodborne illness case in the country's history.

These statistics highlight the unique danger posed by L. monocytogenes.

In the United States, approximately 2,500 cases of listeriosis are reported annually, with around 500 fatalities—equating to a mortality rate of 20%. This alarming fatality rate underscores the critical need for stringent food safety measures to control L. monocytogenes contamination.

Listeria monocytogenes: A Critical Threat to Pregnant Women, the Elderly, and Immunocompromised Individuals

Approximately 40% of Listeria monocytogenes cases occur in pregnant women, with a significant proportion also affecting the elderly. This makes L. monocytogenes unique among foodborne pathogens, as it specifically targets individuals with weakened immune systems, including pregnant women, older adults, and immunocompromised individuals.

For healthy young adults, L. monocytogenes infection often results in mild symptoms such as fever and diarrhea, which are easily mistaken for a common cold. However, in vulnerable populations, these seemingly mild symptoms can quickly escalate:

- Pregnant women: The infection poses a serious risk of miscarriage or stillbirth.

- Older adults: The bacteria can cause life-threatening conditions such as meningitis.

This increased vulnerability is due to weakened immune defenses, making these groups particularly susceptible to severe L. monocytogenes infections.

Mechanism of Severe Infections in the Elderly and Pregnant Women Caused by Listeria monocytogenes

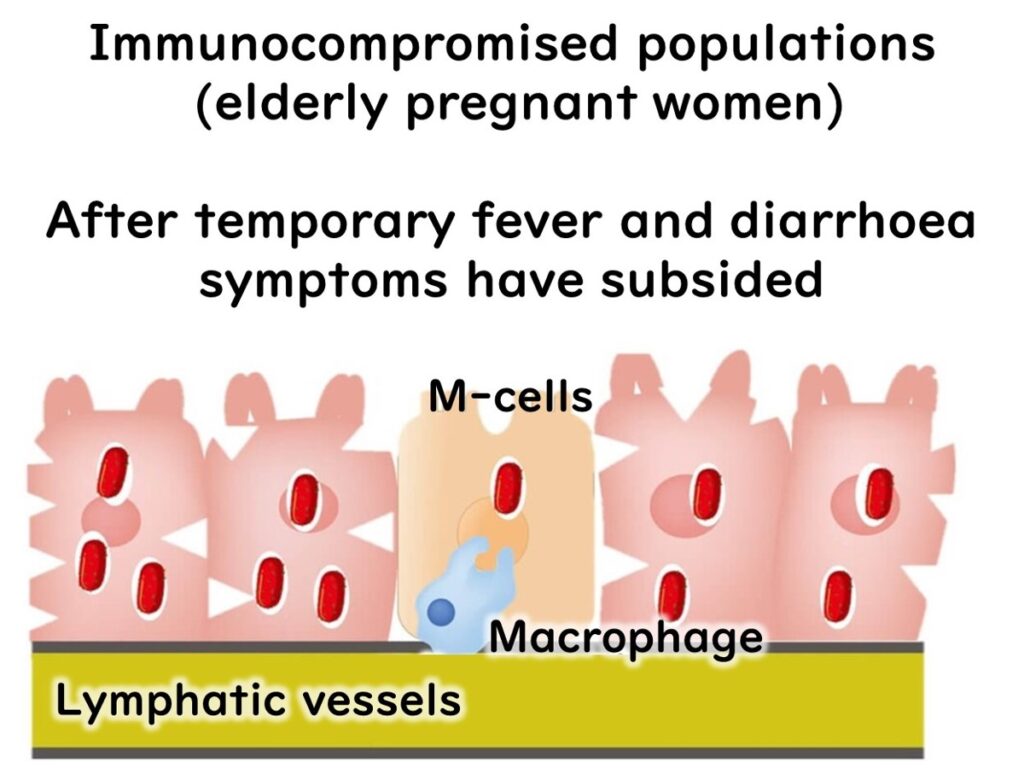

The mechanism by which Listeria monocytogenes causes severe infections in vulnerable individuals such as the elderly and pregnant women is highly complex. Initial symptoms like diarrhea and fever may subside within 24 hours after consuming contaminated food.

However, in individuals with weakened immune systems, a latent period follows before severe symptoms emerge.

Immune System Interaction

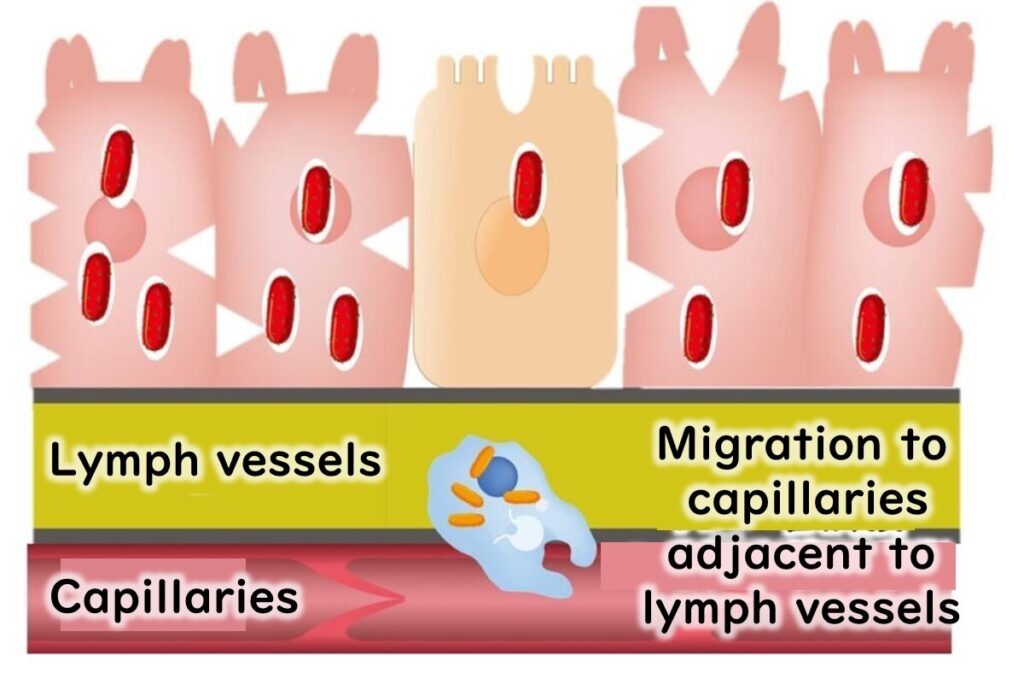

Upon entering the body, L. monocytogenes invades intestinal epithelial cells and is captured by macrophages—immune cells that typically destroy foreign bacteria in lysosomes. In healthy individuals, the bacteria are eliminated at this stage, and symptoms resolve.

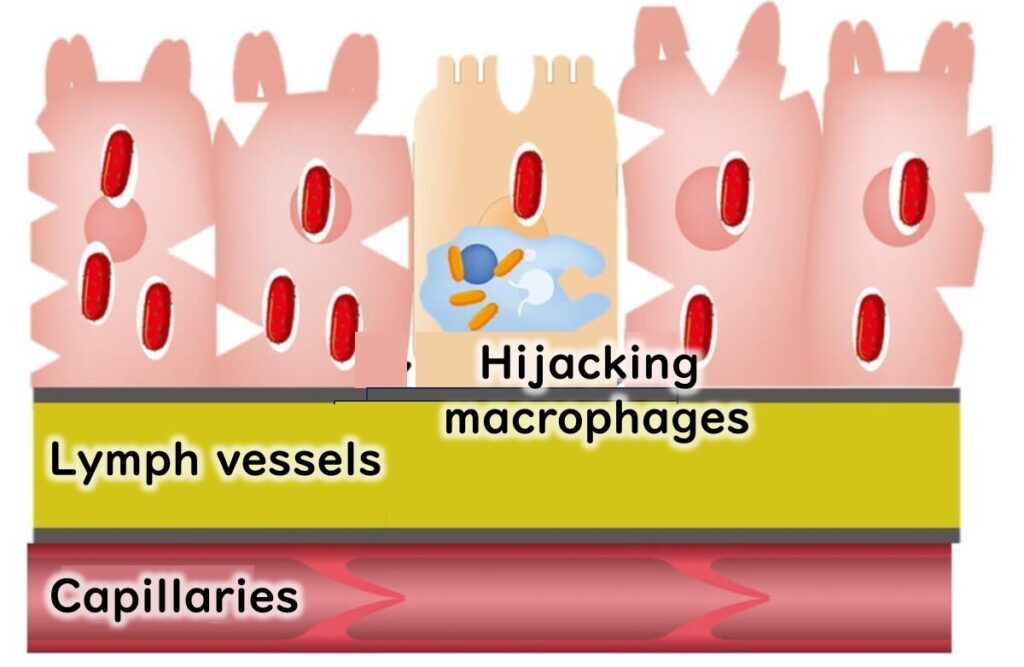

Escape Mechanism

L. monocytogenes has a unique ability to evade destruction. After being engulfed by macrophages, it resides temporarily in a phagosome. Normally, this compartment would fuse with a lysosome containing digestive enzymes to eliminate the bacteria. However, L. monocytogenes produces the enzyme listeriolysin O, enabling it to escape from the phagosome before fusion occurs.

This ability allows the bacteria to survive and multiply within macrophages.

Specific Risks for Vulnerable Populations

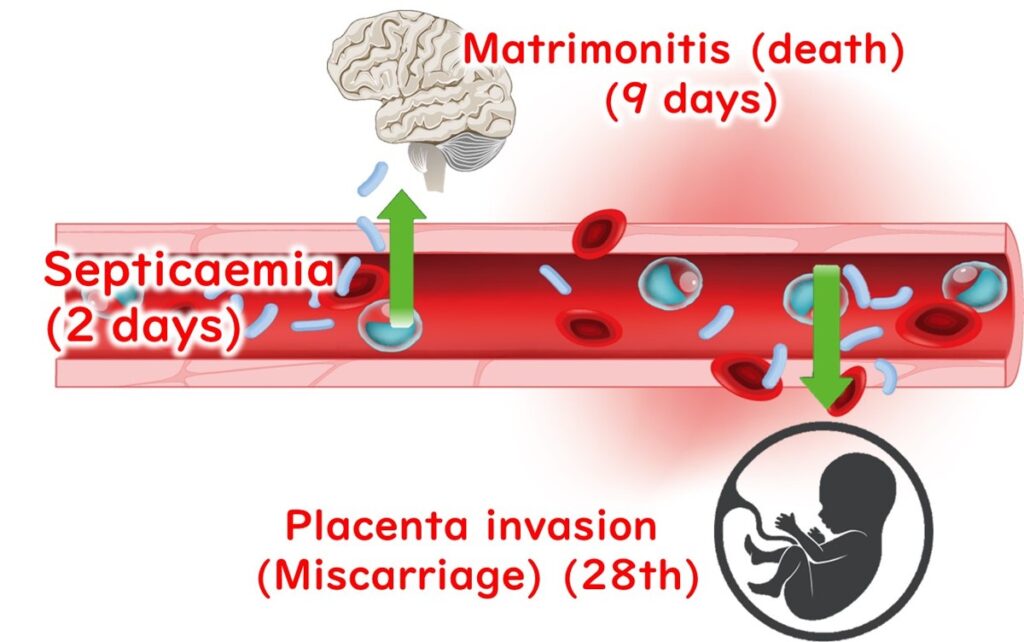

- Elderly: The bacteria can enter the bloodstream and travel to the brain and spinal cord, leading to meningitis and a high risk of mortality.

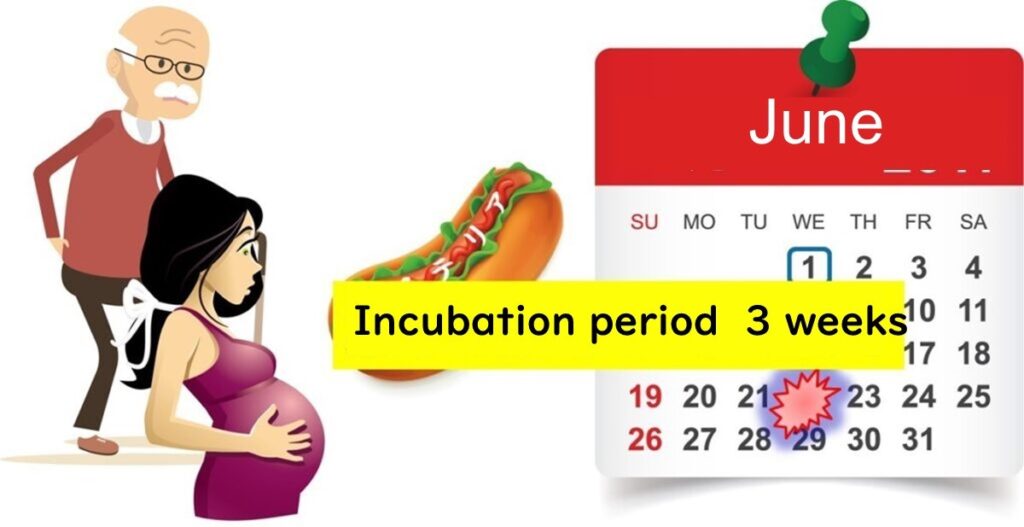

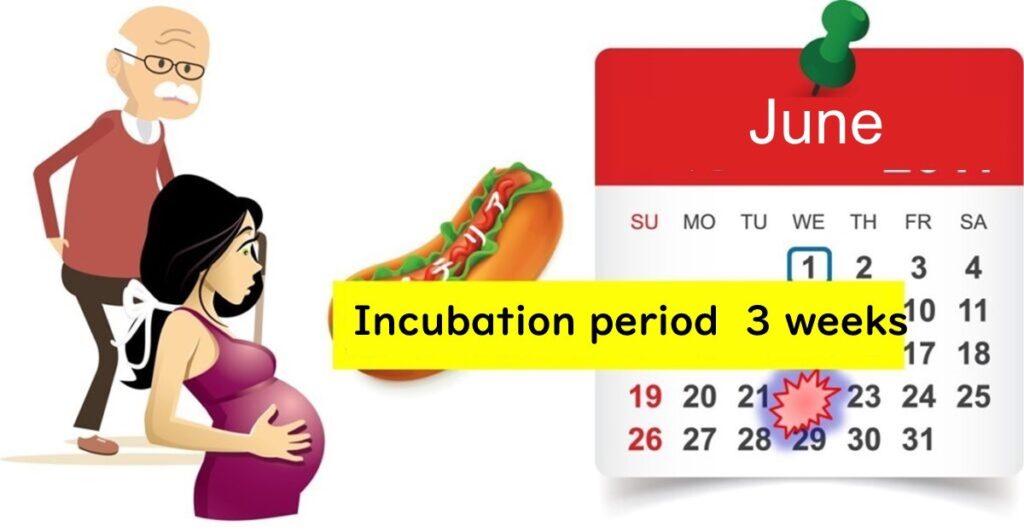

- Pregnant Women: L. monocytogenes can cross the placental barrier, taking up to three weeks to cause complications such as neonatal infections or miscarriage. This delay is attributed to the time required for the bacteria to breach the fetal membranes and invade the amniotic fluid.

The long incubation period, which can extend up to three weeks, complicates the identification of the contaminated food source. This challenge is particularly significant in sporadic cases where only one person in a household develops listeriosis.

Listeria monocytogenes: A Risk Beyond Cured Meats and Cheeses

One of the key distinctions of Listeria monocytogenes compared to other foodborne pathogens, such as E. coli O157, is its ability to survive and multiply in diverse environments. While most foodborne bacteria are Gram-negative and less resistant to environmental stress, L. monocytogenes is a Gram-positive bacterium, granting it remarkable resilience. This adaptability makes preventing L. monocytogenes contamination particularly challenging.

Food Contamination Risks

Certain foods are frequently implicated in L. monocytogenes contamination:

- Cured meats (e.g., prosciutto)

- Raw meats

- Natural cheeses

In the United States and European Union, these foods are often linked to foodborne outbreaks. However, the risk extends beyond these items. All uncooked ready-to-eat (RTE) foods are potential carriers of L. monocytogenes, including:

- Sandwiches made with cured meats or natural cheeses

- Smoked seafood products, such as smoked salmon

In Japan, the prevalence of "raw food culture" increases the risk, with RTE foods like seasoned cod roe (mentaiko) and salmon roe (ikura) frequently contaminated.

Cooking as a Preventive Measure

Low levels of L. monocytogenes contamination in food may be unavoidable. Fortunately, the bacterium is not a heat-resistant, spore-forming pathogen and can be effectively eliminated through standard cooking or pasteurization. However, foods intended for consumption without further cooking (RTE foods) require meticulous handling to minimize the risk of foodborne illness.

The Risk of Long-Stored Foods in the Refrigerator

One concerning characteristic of Listeria monocytogenes is its ability to grow at temperatures as low as 10°C or even lower. This unique trait increases the risk of contamination in foods stored in refrigerators for extended periods.

High-Risk Foods

Ready-to-eat (RTE) foods stored in the fridge and consumed without further heating are particularly vulnerable. High-risk items include:

- Natural cheeses past their expiration date

- Cured meats such as prosciutto

- Smoked seafood, including smoked salmon

- Pre-packaged sandwiches

These foods should be handled with caution, especially if they have been refrigerated for an extended time.

Key Takeaway

To minimize the risk of L. monocytogenes contamination, always check the freshness of refrigerated RTE foods and consider consuming them promptly or heating them when possible.

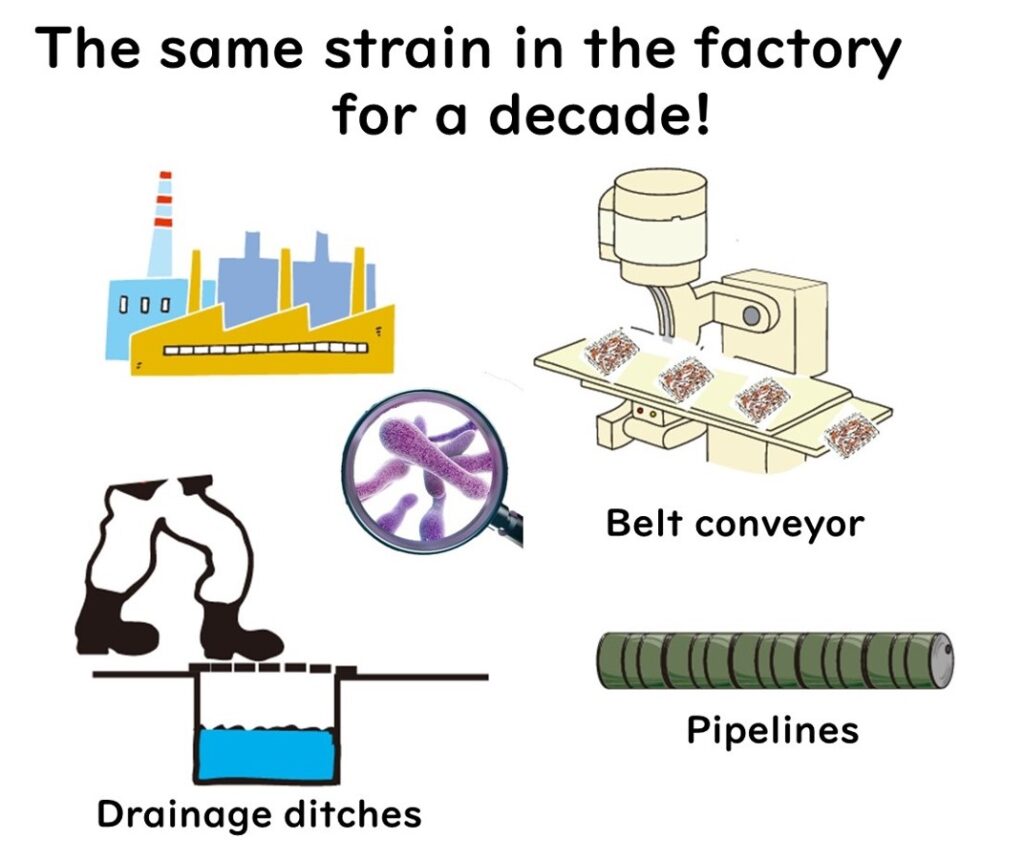

Factory Contamination: The Risk of Listeria monocytogenes

Listeria monocytogenes poses a significant risk in factory environments, particularly in areas like drainage systems. These locations are often cleaned less frequently than production lines or floors due to the challenges of physical scrubbing. As a result, bacteria, including L. monocytogenes, can form biofilms on drain surfaces, creating a robust survival environment.

The Role of Aerosols in Secondary Contamination

When high-pressure hoses are used to clean drainage areas, aerosols may be generated, dispersing fine water droplets into the factory air. These droplets can carry L. monocytogenes, potentially leading to secondary contamination of food products.

Preventive Measures

To mitigate the risk of L. monocytogenes contamination in food production facilities:

- Prioritize frequent and thorough cleaning of drainage systems using appropriate chemical agents and scrubbing techniques.

- Minimize the use of high-pressure hoses in areas prone to aerosol generation.

- Implement regular microbial monitoring to detect and address biofilm formation early.

By adopting these practices, factories can significantly reduce the risk of L. monocytogenes contamination and ensure food safety.

What is the Minimum Infective Dose of Listeria monocytogenes?

The exact dose-response model for Listeria monocytogenes in humans remains incomplete. However, global case data suggest that food containing low concentrations of L. monocytogenes, specifically less than 100 CFU (colony-forming units) per gram, poses minimal risk (FAO/WHO, 2004).

Understanding the Dose-Response Model

A dose-response model estimates the probability of illness based on the amount of pathogen ingested. According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), 92% of listeriosis cases in healthy individuals occur only when the intake exceeds 10⁵ CFU per meal (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2018). This threshold corresponds to:

- An average portion size of 50g, equivalent to a concentration of 2000 CFU/g (2×10³ CFU/g) in cooked food at the time of consumption.

Low Risk at Lower Concentrations

Food with L. monocytogenes concentrations of 100 CFU/g or less—one-tenth of the estimated infective dose—poses minimal risk for healthy adults.

Considerations for Vulnerable Populations

It is crucial to note that these estimates are based on data from healthy adults. Individuals with underlying health conditions or weakened immune systems, such as pregnant women and the elderly, may develop listeriosis at significantly lower bacterial counts. This heightened vulnerability will be discussed in more detail in later sections.

Differing Standards for Listeria monocytogenes in Food: US vs. EU

The United States and the European Union have distinct regulatory standards for the permissible levels of Listeria monocytogenes in food, reflecting different approaches to managing the associated risks.

United States: Zero Tolerance Policy

The U.S. adopts a stringent zero tolerance policy for L. monocytogenes:

- No more than 1 CFU per 25g of food is permitted, equivalent to <0.04 CFU/g.

- This effectively means that the presence of L. monocytogenes is not allowed in any detectable amount.

European Union: Risk-Based Tolerance

The EU allows up to 100 CFU/g of L. monocytogenes in food, with the standard divided into two categories:

- Foods that do not support bacterial growth

- Includes foods with controlled water activity (aw) or pH levels that inhibit L. monocytogenes growth.

- Up to 100 CFU/g is permissible.

- Foods that can support bacterial growth

- For such foods, manufacturers must ensure that the concentration of L. monocytogenes does not exceed 100 CFU/g at any point before the use-by date, provided the product is consumed within its shelf life.

Comparison and Implications

These differing standards highlight the contrast in risk management approaches between the U.S. and the EU:

- The U.S. prioritizes maximum caution with a zero tolerance policy.

- The EU adopts a more flexible, science-based approach that considers food characteristics and storage conditions.

Why Does the US Enforce Zero Tolerance While the EU Allows Up to 100 CFU/g for Listeria monocytogenes?

The European Union's tolerance of up to 100 CFU/g of Listeria monocytogenes is based on risk assessments considering the minimum infective dose for healthy adults, as outlined earlier.

Why the US Adopts a Stricter Approach

In contrast, the United States enforces a zero-tolerance policy for L. monocytogenes, primarily due to reported cases of listeriosis in immunocompromised individuals. These cases occurred even when contamination levels were below 100 CFU/g, demonstrating heightened risks for vulnerable populations.

Notable Cases

Examples of infections linked to low bacterial counts include:

- McLauchlin et al. (2021):Listeriosis associated with pre-prepared sandwich consumption in hospital in England, 2017 (Epidemiol Infect. 149: e220)(2021)

- Pouillot et al. (2016): Infectious Dose of Listeria monocytogenes in Outbreak Linked to Ice Cream, United States, 2015 (Emerg Infect Dis. 22(12): 2113–2119).

Challenges of the Zero-Tolerance Policy

The US zero-tolerance policy results in frequent food recalls, often occurring on a monthly basis. Despite these measures, the overall incidence of listeriosis in the US has not shown a significant decline, highlighting the limitations of this strict approach.

Criticism and Calls for Reevaluation

Criticism of the policy's inflexibility has grown over time. In 2021, researchers from institutions in Canada and the US published a paper advocating for a shift towards internationally aligned standards, such as those of the EU. The study emphasized the need for a more balanced approach to managing risks in low-risk foods:

- Farber et al. (2021): "Alternative Approaches to the Risk Management of Listeria monocytogenes in Low-Risk Foods" (Food ControlVolume 123, May 2021, 107601).

What Are the Standards for Listeria monocytogenes in Japan?

In Japan, regulatory standards for Listeria monocytogenes exist only for two specific categories of food:

- Natural Cheeses

- Non-heat-treated Meat Products (such as prosciutto)

No Standards for Other RTE Foods

Unlike the United States and the European Union, Japan has not established specific standards for other ready-to-eat (RTE) foods. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare attributes this to the low reported incidence of listeriosis in Japan. Statistically, only one officially recognized case of listeriosis has been documented, which has reduced the perceived need for broader regulations.

Regulatory Changes in 2014

Prior to 2014, Japan adhered to a zero-tolerance policy similar to that of the United States, permitting no more than 1 CFU per 25g of food for the two regulated categories. However, in 2014, compositional standards were revised to align with the European Union and the Codex Alimentarius (CODEX). This change allowed up to 100 CFU/g of L. monocytogenes in natural cheeses and non-heat-treated meat products.

Harmonization with International Standards

The 2014 revision reflects Japan's efforts to harmonize its food safety regulations with international guidelines, particularly those set by CODEX. This alignment ensures consistency in global food trade and reinforces Japan's commitment to international food safety standards.

Codex Alimentarius (CODEX) Guidelines for Managing Listeria monocytogenes

The Codex Alimentarius, commonly referred to as the "Food Code," provides internationally recognized guidelines for managing Listeria monocytogenes in food products. These guidelines include the following:

- For Foods Where L. monocytogenes Can Grow

- A zero-tolerance policy applies (L. monocytogenes must not be detected in 25g of the product).

- For Foods Where L. monocytogenes Cannot Grow

- Up to 100 CFU/g is permissible.

- Additional Flexibility

- Regulatory authorities can implement flexible standards to ensure consumer safety.

- For foods capable of supporting L. monocytogenes growth during distribution, manufacturers must set the use-by date so that the bacterial concentration does not exceed 100 CFU/g by the time the product is consumed.

Application of Codex Guidelines

- European Union: Fully adheres to points 1, 2, and 3.

- United States: Implements only point 1 (zero tolerance).

- Japan: For natural cheeses and non-heat-treated meat products, follows point 3, ensuring that L. monocytogenes does not exceed 100 CFU/g by the time the product reaches consumers.

Rationale for Japan's Approach

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare decided to apply point 3 to natural cheeses and non-heat-treated meat products due to the uncertainty about whether these foods can completely inhibit L. monocytogenes growth. As a result, manufacturers are required to ensure that the concentration remains below 100 CFU/g at the time of consumption.

Assessing the Risk of Listeria monocytogenes in Japan

In Japan, foodborne illnesses caused by Listeria monocytogenes are officially recorded as extremely rare, with only one confirmed case reported to date. This has fostered a perception that L. monocytogenes contamination is nearly nonexistent in the country.

However, a nationwide clinical survey presents a different reality:

- Approximately 83 cases of listeriosis occur annually, equating to 0.65 cases per 1 million people.

- The majority of infections occur in:

- Infants under one year of age.

- Elderly individuals, particularly those over 70, who experience a high fatality rate of 20%.

Reference:

Okutani et al., Nationwide Survey of Human Listeria monocytogenes Infection in JapanEpidemiol. (Epidemiol. Infect. 132:769–772, 2004).

Challenges in Identifying Infection Sources

The sources of listeriosis infections in Japan remain largely unknown. Sporadic cases involving one or two individuals make it nearly impossible to identify the cause unless the same genetic strain of L. monocytogenes is detected in food samples from the patient’s home.

This uncertainty poses significant challenges for ensuring food safety and highlights the need for:

- Continued vigilance in monitoring and controlling contamination risks.

- Ongoing research to better understand L. monocytogenes transmission pathways and develop effective prevention strategies.

Conclusion: Key Strategies for Managing Listeria monocytogenes

Contamination with Listeria monocytogenes can potentially occur in any food product, and completely preventing its intrusion remains a significant challenge. For food manufacturers, effective management of L. monocytogenes involves the following key strategies:

- Preventing Biofilm Formation

- In food production facilities, preventing biofilm formation is a critical step.

- Stringent hygiene and sanitation practices are essential, as biofilms can serve as a persistent source of contamination.

- Controlling Contamination in Ready-to-Eat (RTE) Foods

- RTE foods, which may already contain L. monocytogenes due to unavoidable contamination during raw material procurement, require special attention.

- The primary focus should be on preventing bacterial growth during storage and distribution.

- Adhering to Microbial Standards

- Standards in the EU and Japan allow up to 100 CFU/g of L. monocytogenes at the product’s use-by date for certain foods, such as natural cheeses and non-heat-treated meat products.

- Instead of merely adhering to this upper limit, manufacturers should aim to maintain L. monocytogenes concentrations as low as possible.

- Innovative microbial control methods are needed to prevent even low-level contamination from escalating during distribution and storage.

Summary: Key Points in Listeria monocytogenes Management

Managing Listeria monocytogenes involves more than just preventing its initial entry into food products. It requires controlling its growth and spread throughout the food production and distribution process. By implementing rigorous sanitation practices and advanced microbial control strategies, manufacturers can significantly reduce the risks associated with L. monocytogenes in food products.