When interpreting standards for standard plate count (SPC) in food, it’s crucial to understand that the method of testing and measurement can vastly influence the outcome. In fact, the definition itself might change! This article highlights the methods used to test for standard plate count in food, with a special focus on contrasting approaches between the United States (AOAC method) and the European Union (ISO method), emphasizing the broader international discrepancies. Don your lab coats and prepare for a microscopic adventure into the world of food microbiology, where every detail can lead to a world of difference!

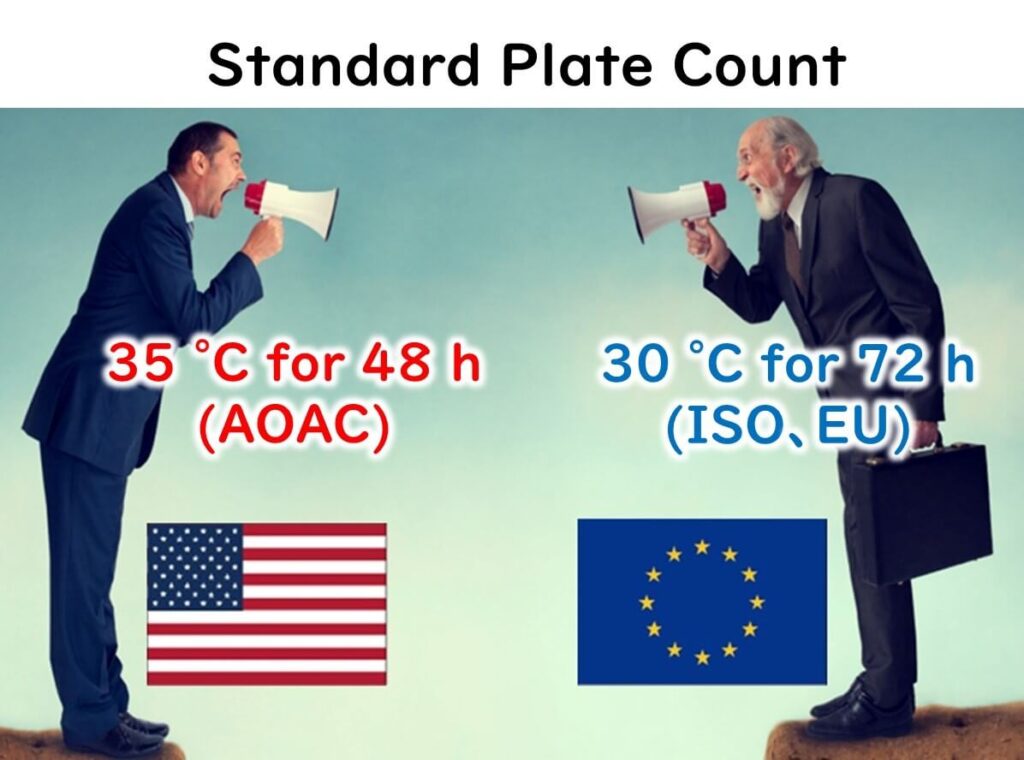

Global Division in Standard Conditions for Measuring General Bacterial Counts

Globally, the standards for measuring general bacterial counts are essentially divided between the American system (AOAC method) and the European Union (EU) system (ISO method).

- American System (AOAC Method) Temperature: 35°C Duration: 48 hours (Note: This method is adopted by Japan as well.)

- European Union (ISO Method) Temperature: 30°C Duration: 72 hours

In Japan, the standards under the Food Sanitation Act follow the American method.

Note: The AOAC method is widely used in food analysis in various countries, including the United States, Latin America, and Japan. AOAC International is an organization centered in the U.S., composed of scientists and regulatory officials involved in the validation and quality control of various analytical methods. In the food sector, the so-called AOAC methods are detailed in the "Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL."

Both methods have their pros and cons.

Advantages of the ISO Method

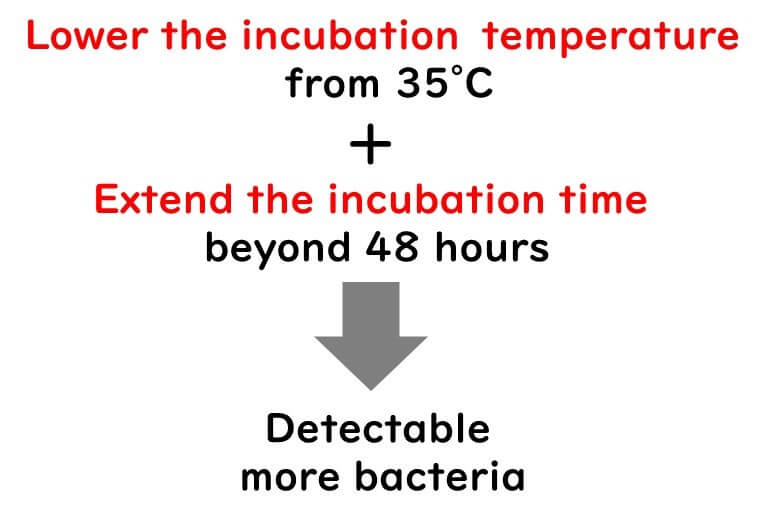

Generally, lowering the incubation temperature and extending the cultivation time can result in a higher bacterial count.

For instance, a study on milk has shown that the ISO method (30°C, 72 hours) can achieve bacterial counts that are 0.18 log higher than those obtained with the AOAC method (35°C, 48 hours) (refer to the literature below). This is a point in favor of the ISO method.

Do different standard plate counting (IDF/ISSO or AOAC) methods interfere in the conversion of individual bacteria counts to colony forming units in raw milk?

J Appl Microbiol.121(4):1052-8(2016)

Advantages of the American Method (AOAC Method)

On the other hand, when it comes to indicators like general bacterial counts, speed is of the essence.

In terms of rapidity, the AOAC method takes the cake.

A Rough History of Total Viable Count Measurement

Let’s unravel a bit of the global history of general bacterial counts. While this will be a broad overview, it serves to understand the major trends.

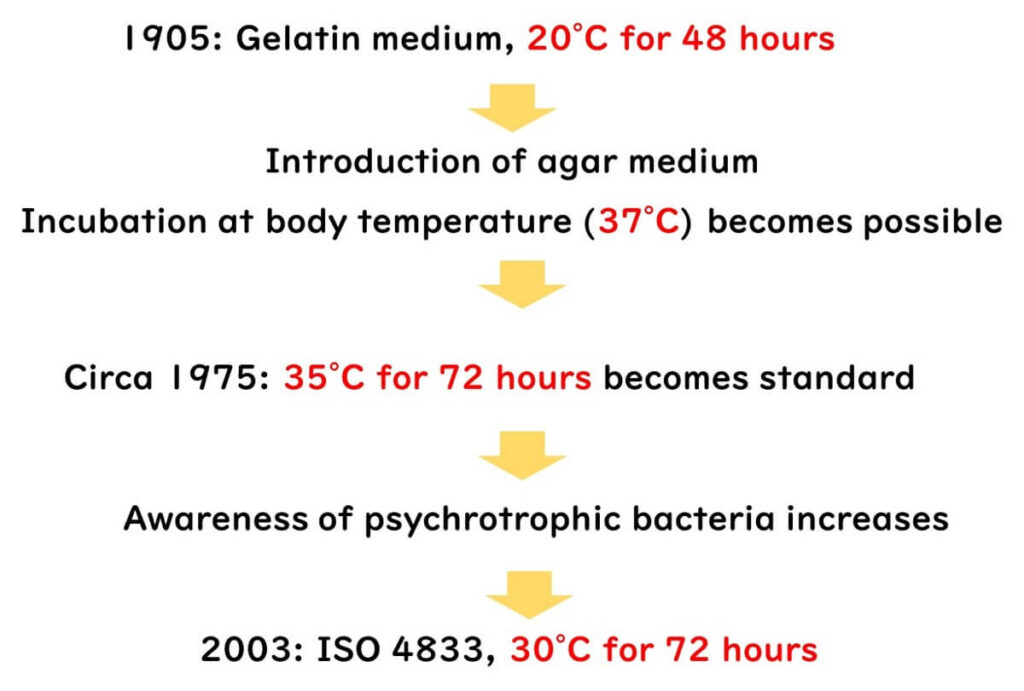

Initially, in 1905, gelatin media were developed for bacterial cultivation. Due to gelatin’s melting point, higher temperatures could not be used, thus standardizing the practice of incubating at 20°C for 48 hours. However, with the introduction of agar media, which could withstand higher temperatures, a shift occurred. Considering the microbial environment of the human intestine, which the general bacterial count aims to reflect, a cultivation temperature of 37°C began to be adopted. By around 1975, the norm had become 35°C for 72 hours.

However, as chilled food distribution became more common, the presence of psychrotrophic (cold-loving) bacteria was increasingly recognized. This recognition led to the adoption of 30°C for 72 hours in the 2003 ISO 4833 standard. Since then, the ISO method has maintained these conditions, while the American method (AOAC) continues to use 35°C for 48 hours up to the present day.

While the details may vary, this is roughly the historical flow of standard practices in measuring general bacterial counts.

Cultivation Temperatures and Durations Used by Researchers

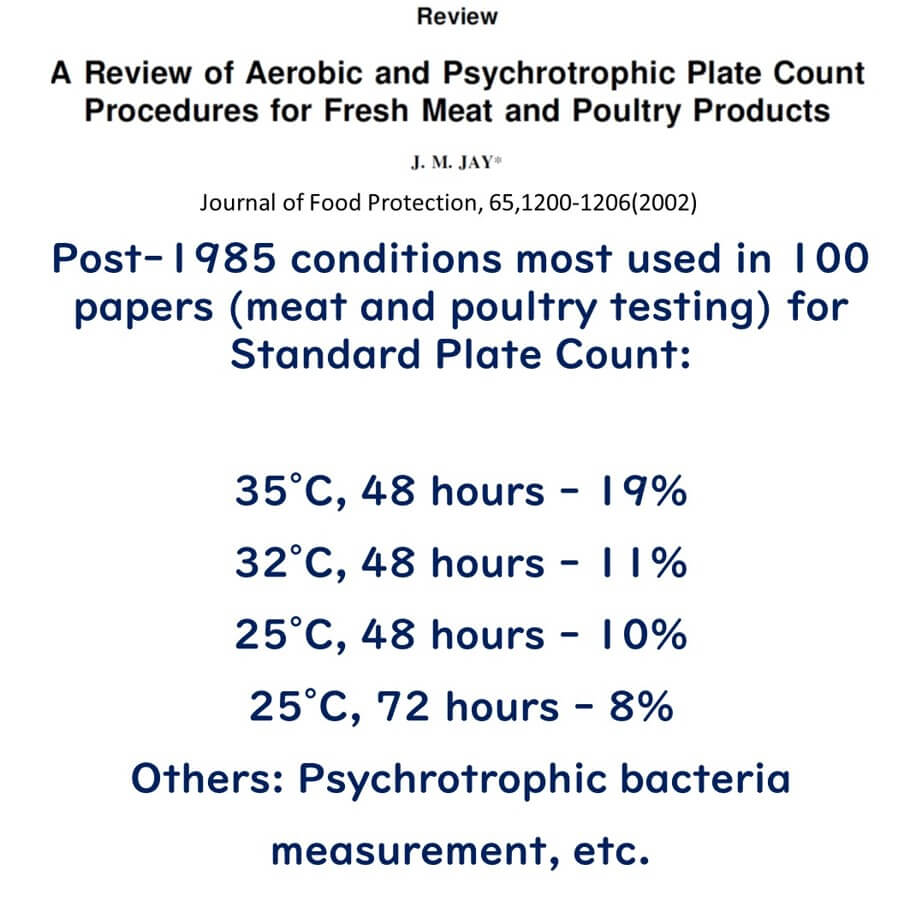

Setting aside legal standards, what are the common conditions for measuring general bacterial counts in academic research papers? The answer can be found in the following paper:

A Review of Aerobic and Psychrotrophic Plate Count Procedures for Fresh Meat a

A Review of Aerobic and Psychrotrophic Plate Count Procedures for Fresh Meat and Poultry Products

J Food Prot;65(7):1200-6 ( 2002)

This paper reviews research articles from 1985 to 2002 that measured general bacterial counts in meat and poultry. It compiles and organizes the cultivation conditions used. The most commonly used conditions, listed in order of frequency, are: