Discover how noroviruses impact food safety through their unique characteristics and surprising survival strategies. This article explores their transmission routes, resilience, and practical methods to prevent norovirus food poisoning.

Norovirus Characteristics: A Domino Effect of Understanding

To fully understand noroviruses, it's essential to start with their unique habitats. By exploring their habitats first, we can sequentially uncover their other characteristics, much like a domino effect.

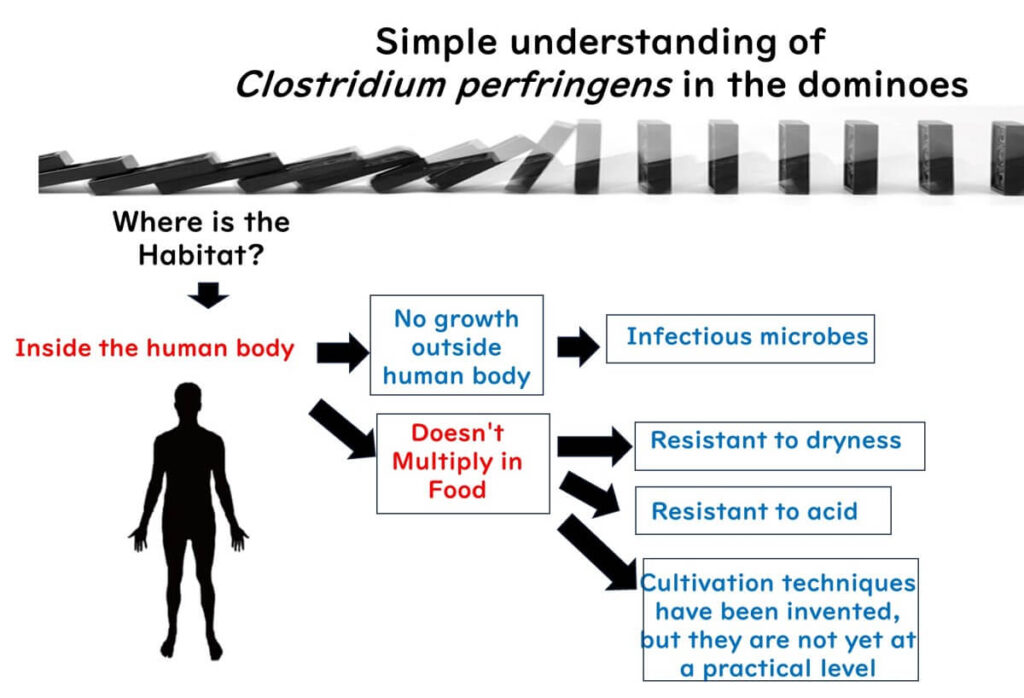

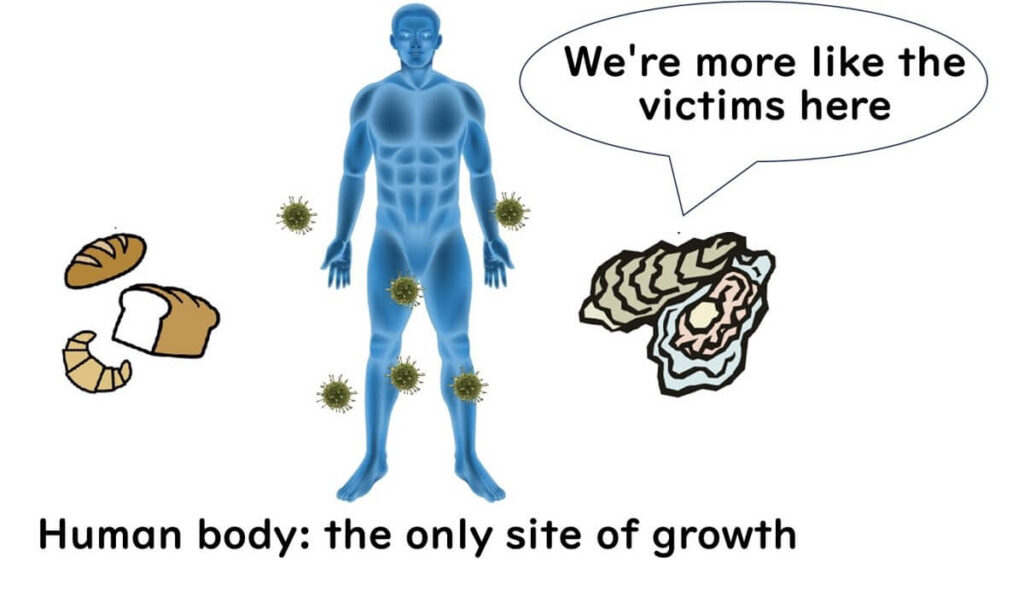

- Exclusive Habitat: The only place where noroviruses can multiply is inside the human body. This is a fundamental concept in food hygiene management.

- No Gram Staining: Noroviruses, being viruses, lack Gram staining properties, distinguishing them from bacteria.

- Classification: Noroviruses are classified as infectious microbes.

- No Multiplication Temperature: Noroviruses do not multiply outside the human body. In food or environmental surfaces, they exist as particles, highly resistant to physical stress like dryness.

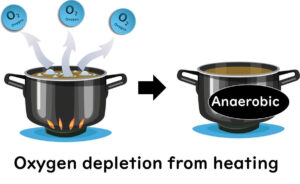

- Oxygen Independence: Noroviruses do not require oxygen for multiplication, as they cannot reproduce in food or environmental conditions.

- Acid Resistance: Noroviruses are highly resistant to acid, allowing them to survive stomach acid and reach the small intestine. Even minimal contamination can lead to infection.

- No Role for Antimicrobials: Antimicrobials are ineffective against noroviruses since they cannot multiply in food.

- No Selective Media: Noroviruses cannot be cultivated using selective media. While laboratory-level cultivation has been reported, it is not yet a practical technique.

By understanding these characteristics sequentially, much like toppling dominoes, we gain a clearer picture of noroviruses and their unique traits.

How Norovirus Spreads: Human Roles and Contamination Routes

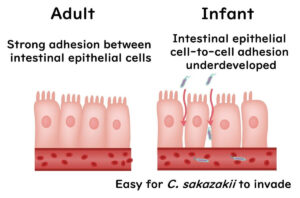

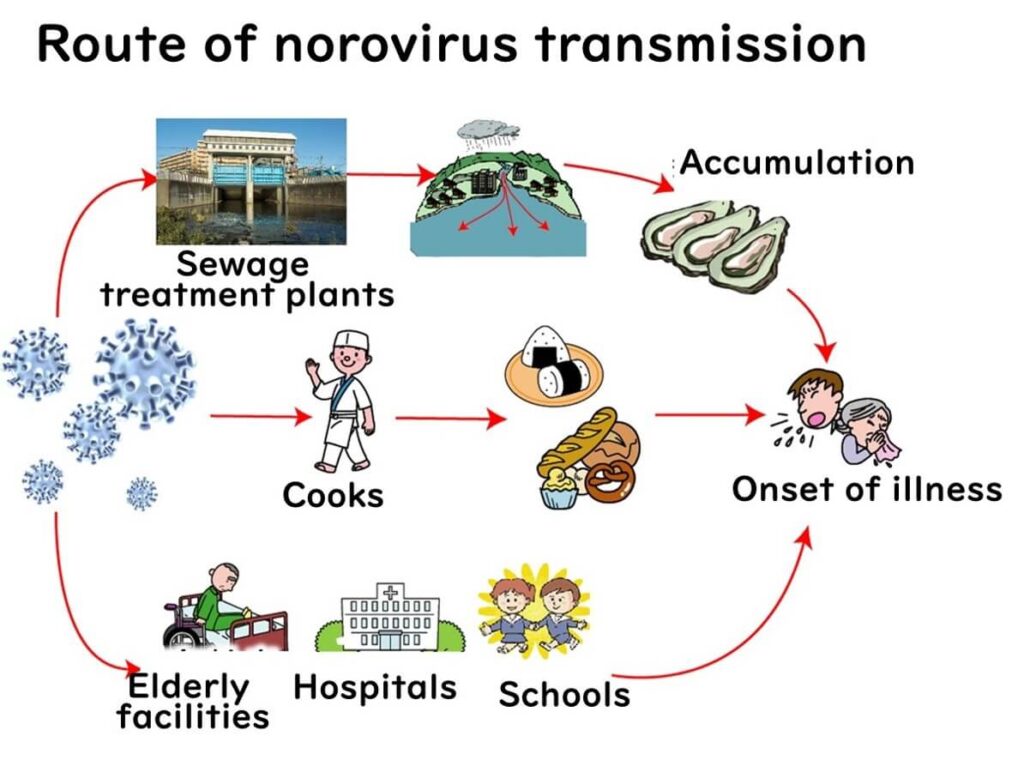

Noroviruses behave more like inert particles rather than living organisms outside human host cells. Once they infect human intestinal cells, they multiply rapidly and burst out of the cells. This highlights a critical fact: humans are the sole hosts for noroviruses. Consequently, human activities are the primary cause of food contamination by noroviruses.

For example, while oysters are often associated with food poisoning, they are not natural habitats or breeding grounds for noroviruses. Contamination occurs when untreated or partially treated wastewater carrying noroviruses flows into rivers and eventually reaches the sea. Bivalves like oysters, which filter and consume plankton from seawater, inadvertently accumulate noroviruses. Importantly, noroviruses do not multiply within oysters.

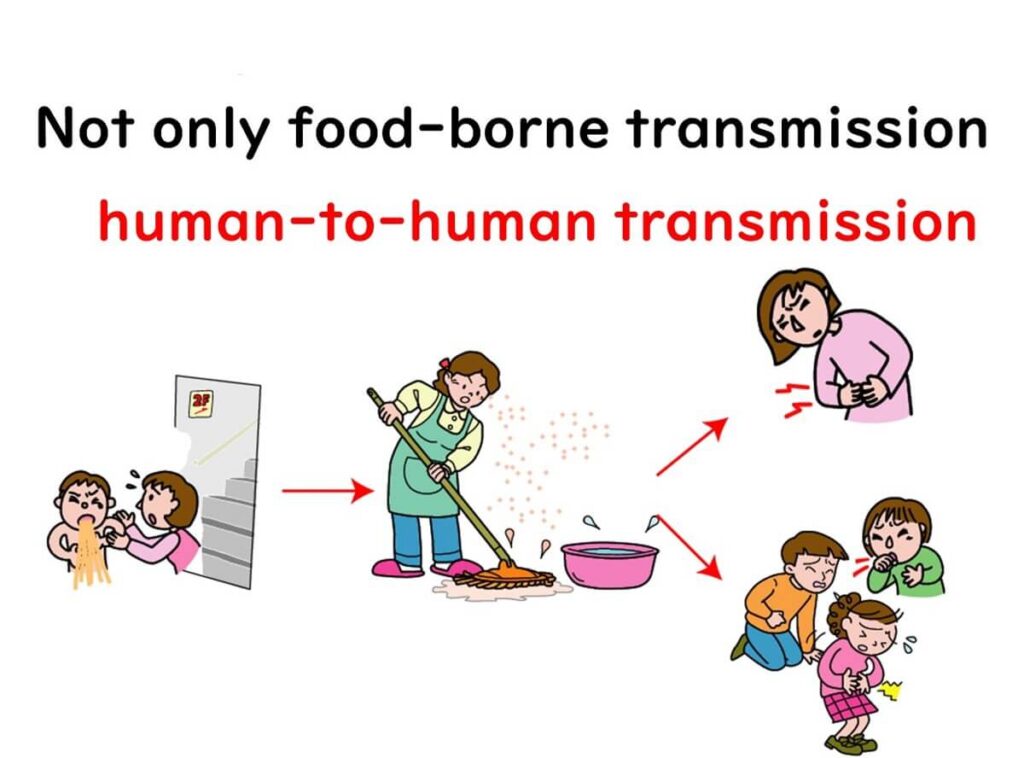

Another major route of contamination is direct transfer from human hands, such as when food factory workers handle products like bread. Unlike bacteria, noroviruses can remain infectious on dry food surfaces, making contamination by human contact a critical concern.

Additionally, person-to-person transmission is a significant route. Noroviruses can survive for up to three hours in stomach acid at a pH of 3, meaning even a small number of virus particles can cause infection. Beyond food, transmission can occur through contaminated air, objects like towels, or direct contact, raising the question: Should noroviruses even be classified strictly as foodborne pathogens?

Key Symptoms and Risks of Norovirus Infection

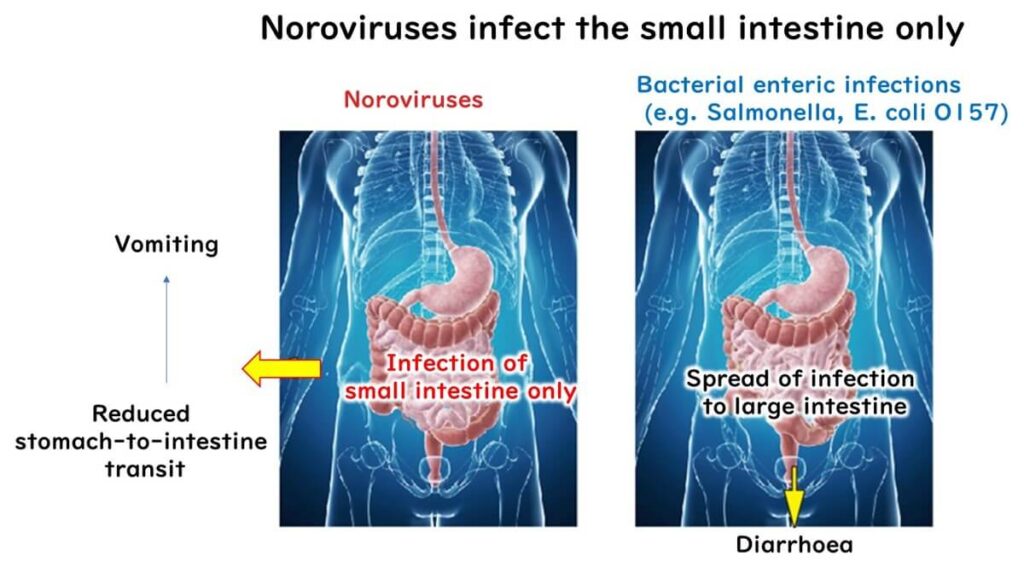

The most distinctive symptom of a norovirus infection is vomiting, as the infection typically targets the upper part of the small intestine. Once noroviruses pass through the stomach and reach the small intestine, the infection begins almost immediately.

The body's natural defense mechanism tries to expel the virus, resulting in vomiting rather than diarrhea. This is because the infection is localized closer to the mouth than the anus.

In contrast, bacterial food poisoning typically begins in the small intestine but may spread to the colon, leading to diarrhea. This key difference underscores the unique nature of norovirus infections compared to bacterial infections.

How Healthy Individuals Can Spread Norovirus Without Knowing

Even after recovering from norovirus food poisoning, individuals continue to shed the virus in their stool for about a week. This means their hands can still carry noroviruses, even if they feel well. If such individuals work in food production or retail, there is a significant risk of contaminating food products. To minimize this risk, employees diagnosed with norovirus are typically advised to avoid food production for at least a week.

Another critical factor is that both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals excrete similar amounts of the virus. While symptomatic patients spread the virus more efficiently through vomiting, asymptomatic carriers pose a silent threat in food production environments. This dual challenge underscores the complexity of controlling norovirus spread in the food industry.

Why Norovirus Cannot Multiply in Food: Key Insights

Since humans are the sole hosts for noroviruses, these viruses do not multiply in food. This means that common food storage strategies, such as refrigeration or low-temperature storage, do not prevent norovirus food poisoning.

Similarly, developing preservatives to inhibit norovirus growth in food is not feasible. I once asked a university colleague if they were interested in researching preservatives to prevent norovirus growth in food.

Although enthusiastic at first, they soon discovered the concept was irrelevant—noroviruses do not proliferate in food at all.

The only effective strategy to mitigate norovirus risk is to ensure that potentially infected individuals do not come into contact with food. This prevention strategy is notably different from the approaches used for managing other foodborne pathogens.

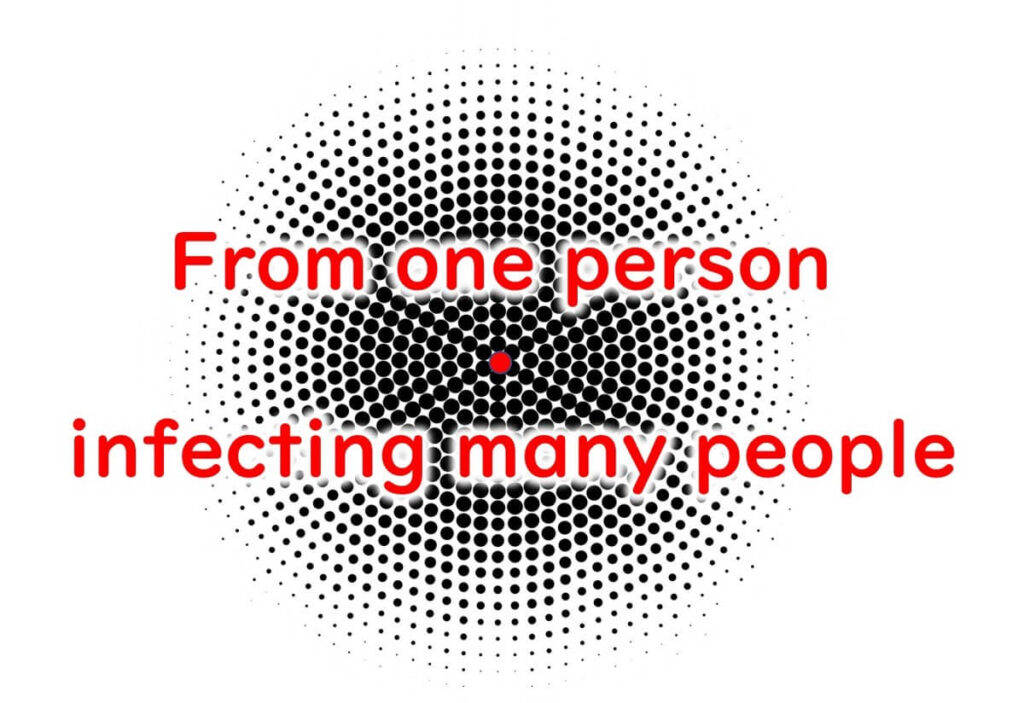

Norovirus in Dry Conditions: How One Source Can Infect Thousands

A defining characteristic of noroviruses is their ability to cause widespread infection from a single contaminated source. A striking example is the norovirus outbreak in Tokyo in February 2017, involving contaminated chopped seaweed. This incident led to 1,193 students and staff at an elementary school falling ill.

Investigations revealed that the seaweed had likely been contaminated two months earlier, in December 2016, by an elderly subcontractor in Osaka who handled the seaweed with bare hands. During interviews, the worker recalled feeling unwell, like having a cold, at the time.

This outbreak highlights two crucial points:

- Noroviruses can retain their infectiousness for at least two months in dry conditions.

- A single contaminated source can infect over a thousand people.

Such incidents emphasize the importance of strict hygiene practices, especially when handling food products, to prevent similar large-scale outbreaks.