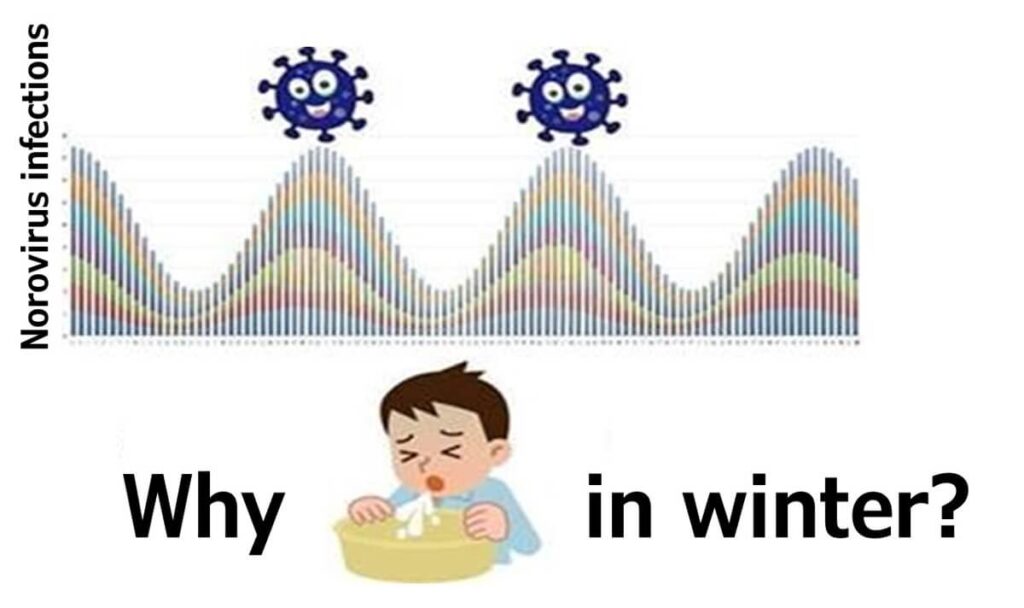

In temperate regions, bacterial food poisoning incidents typically peak from early summer to autumn. This surge is due to the favourable warm temperatures that facilitate the growth of pathogenic bacteria in food. Conversely, norovirus infections are more prevalent in winter. Why is this? Is it because we eat oysters in winter? Does the virus become more potent in the cold? Until recently, the scientific data was insufficient to provide clear answers. However, the study we are discussing in this article offers a potential explanation.

Colas de la Noue et al.

Absolute Humidity Influences the Seasonal Persistence and Infectivity of Human Norovirus

Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 7196–7205(2014)

Open access

Why Does Norovirus Peak in Winter?

Historically, raw oysters were considered the main cause of norovirus food poisoning, leading some to believe the winter spike was due to increased oyster consumption during this season. Yet, norovirus outbreaks aren't limited to oysters alone; infected individuals can contaminate various foods with the virus.

Additionally, the pattern of increased winter norovirus cases is observed in many temperate countries. Since humans—being warm-blooded hosts—are the sole proliferative environment for norovirus, the seasonal link has remained a mystery.

The research we are discussing today provides one possible answer to this question.

Research Findings from Burgundy University

Dr. Noue and colleagues at Burgundy University in France investigated why norovirus food poisoning is more common in winter by focusing on absolute humidity (AH) levels in the environment.

Since human norovirus cannot be cultured in a laboratory, the team used mouse norovirus (MNV) for their experiments. They examined the virus's survival at 9 °C and 25 °C across a range of relative humidity levels (RH), from low (10% RH) to saturated (100% RH).

They also conducted similar experiments using virus-like particles (VLPs) from the predominant GII-4 norovirus strain. These experiments analysed changes in the binding patterns to A, B, and O blood group antigens, which serve as indicators of changes in the virus's capsid protein.

Their findings showed that both norovirus and the VLPs responded similarly to humidity:

- Infectivity and binding ability were well preserved at 10% and 100% RH,

- But significantly reduced at 50% RH.

In essence, norovirus survival and infectivity suffer at intermediate humidity levels (around 50% RH), but are best preserved at both low and high extremes of relative humidity. Notably, extreme high humidity also enhances viral persistence.

Absolute Humidity: A Key Factor

Dr. Noue's research further revealed that absolute humidity (AH)—rather than relative humidity (RH)—is more closely associated with norovirus infectivity.

Specifically, norovirus thrives when absolute humidity levels fall below 0.007 kg of water per kg of air.

An analysis of 14 years of weather data from Paris revealed that winter average AH consistently drops below this threshold (ranging from 0.0046 to 0.0014 kg of water per kg of air).

From these findings, the researchers concluded that the primary reason for the seasonal prevalence of norovirus in winter is the low absolute humidity during this time of year.

My Take on This Study

From my perspective, the key takeaway is that this research challenges the long-standing assumption that norovirus is relatively unaffected by humidity. What struck me most in this study is the discovery that, despite being a non-enveloped virus, norovirus shows a clear preference for dry conditions—much like the influenza virus, which is enveloped.

This finding is particularly significant because it helps explain why norovirus persists in winter, independent of oyster consumption or foodborne vectors. It shifts our understanding of environmental influences on norovirus survival, placing absolute humidity—not just temperature or food habits—at the centre of the discussion.

For food industry professionals, especially those working in hygiene control or managing outbreaks, this study underscores the importance of considering environmental conditions like humidity in risk assessments and HACCP-based controls during the colder months.

This aligns with what I have seen in food industry settings, where winter norovirus outbreaks often occur despite rigorous hygiene practices. The low absolute humidity of indoor environments in winter may indeed be a hidden contributing factor.

Further Reading:

For more on how enveloped viruses like influenza are affected by environmental factors, see the linked article on ethanol disinfection and its mechanisms.

Why 70% Ethanol is the Star of Sterilization: Mechanisms and Limitations

For a refresher on the basics of norovirus, please refer to the linked article below.

Norovirus: Characteristics, Transmission Routes, and Effective Prevention