To understand the essential strategies of disinfection and cleaning in a food production facility, consider a hypothetical scenario involving Mr. Yamada, a factory worker. Imagine him attempting to disinfect his boots by immersing them in a disinfectant tray at the factory entrance, despite significant food residue on the soles. This situation highlights a critical insight into microbial disinfection: mere disinfection without proper cleaning is ineffective.

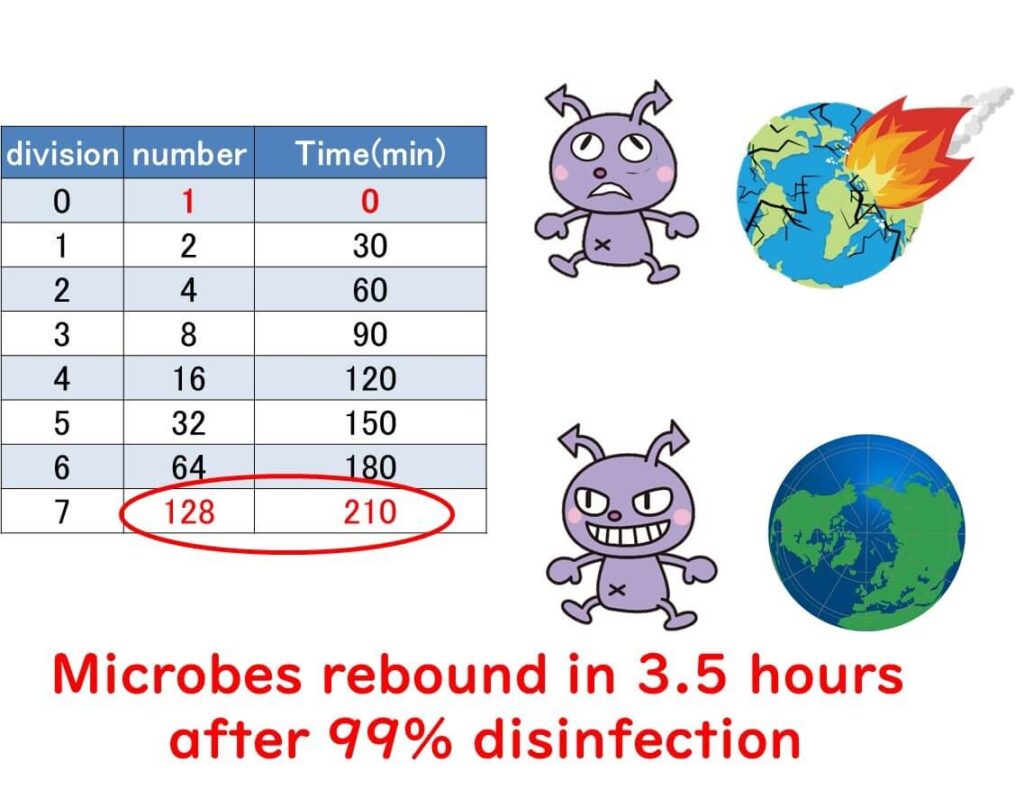

If 99% of microbes are eliminated on boots covered in organic matter, it might seem sufficient—like a catastrophic meteor strike wiping out 99% of Earth's population.

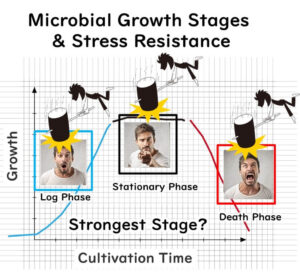

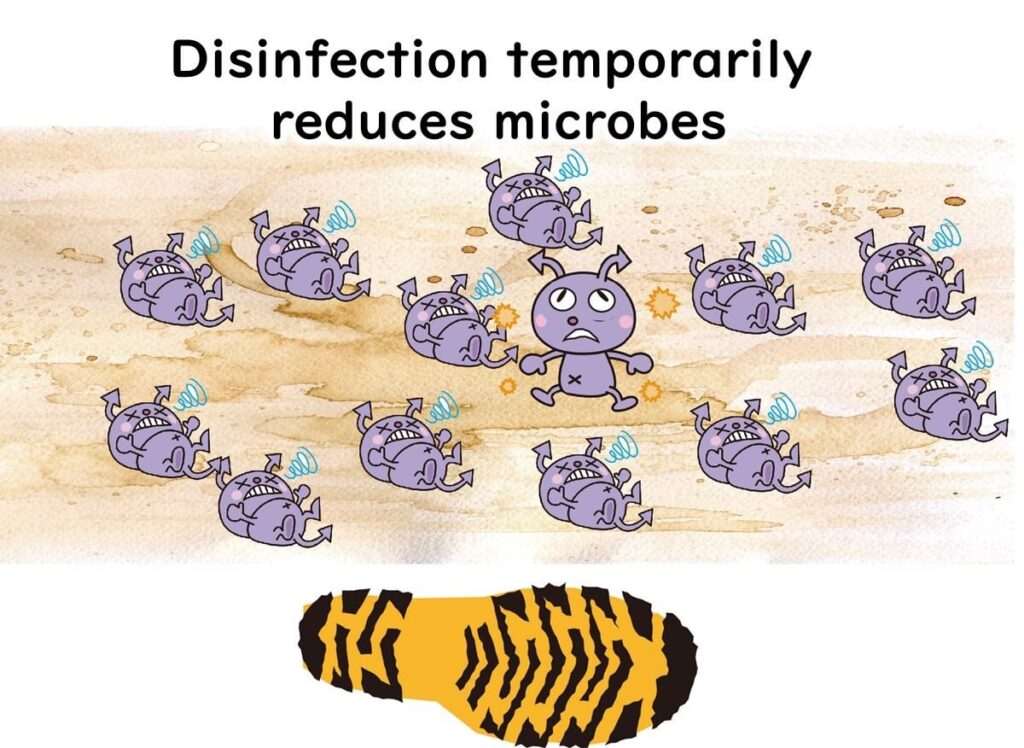

However, microbes are resilient; under optimal conditions, they can double every 30 minutes. In just seven divisions, a single cell can grow to 128 cells, and in about 3 hours, a microbial population can return to its original count or even increase a hundredfold if nutrients and temperature are favorable. Thus, relying solely on disinfection without cleaning is a misguided approach.

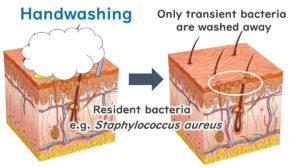

Consider the impact of prioritizing cleaning. Even if some microbes survive, cleaning can remove the nutrients necessary for their growth. In some cases, nutrient deprivation leads to microbial death, making cleaning an essential step before disinfection. Proper cleaning eliminates the organic material microbes require to thrive, setting a solid foundation for effective microbial control. In an ideal process, cleaning should always precede disinfection, as this mindset enhances food safety in factory settings.

Relying solely on disinfection is misplaced. Unless complete sterilization is achieved, common disinfection practices in factories leave behind surviving microbes, emphasizing the need to prevent rapid microbial regrowth by removing organic residues.

Some might think extensive knowledge of disinfectants is enough for effective microbial control in food production. However, a solid understanding of cleaning principles is often more practical. Knowing what to clean, the priority of cleaning areas, and the purpose of cleaning each area forms the foundation of effective food microbiology practices. In many cases, even simple washing with water and soap can contribute significantly to microbial control in food production.